LANDSCAPE PERSPECTIVES:

EQUITY IN + BY DESIGN

SANJUKTA SEN

BENJAMIN C. HOWLAND PANEL 2019

Below is an annotated transcript of Sanjukta Sen’s lecture for the 2019’s Benjamin C. Howland Panel. Thank you to the UVA faculty and students that sent annotations and comments. Initial key for annotators can be found on the lower navigation panel.

I’m going to talk to this issue of access and equity through a few projects that I have worked on in my time at James Corner Field Operations. I want to think through these projects through the lens of diversity, demographics, and related to demographics, the history of sites and how sites are perceived as we take them from one state, and transform them to become parks and public places that are changed tremendously. The four projects I wanted to talk about live in the realm of public / private development. They all have either developers, institutions, or city agencies as our clients.

In some ways, the ways we interact with the public is a sort of managed interaction, and in that framework, how we set up the goals of access, equity, sustainability is something that has been an interesting evolution for us as a practice. The first project I want to talk about is the Cornell Tech Campus on Roosevelt Island in New York. It’s about a 12 acre site on the southern tip of Roosevelt Island, which is almost like a mini Manhattan, if you will. It used to actually be called “Welfare Island,” because of the number of hospitals that used to be there. A lot of invalids and people with smallpox were sent there. So the perception of this specific tract of the island was of disease.

In some ways, the ways we interact with the public is a sort of managed interaction, and in that framework, how we set up the goals of access, equity, sustainability is something that has been an interesting evolution for us as a practice. The first project I want to talk about is the Cornell Tech Campus on Roosevelt Island in New York. It’s about a 12 acre site on the southern tip of Roosevelt Island, which is almost like a mini Manhattan, if you will. It used to actually be called “Welfare Island,” because of the number of hospitals that used to be there. A lot of invalids and people with smallpox were sent there. So the perception of this specific tract of the island was of disease.

When Cornell won the competition to put their tech campus on the site, part of the task was: how do you change the perception of something that used to be related to hospitals and smallpox into something that would be absorbed back into the public realm of the city? The other distinguishing factor about the site was the fact that it has escaped the density of Manhattan. It is Manhattan, but does not have the crazy density. However, because of its proximity to the United Nations, it has a great amount of diversity. So balancing those elements was an interesting task. What Cornell did promise us was that every building would be designed by a “starchitect”. So we thought of our design as a flexible a framework that would reign our starchitect friends in a little bit, but would also set up a really robust framework for the future development of the campus, which is slated to evolve over 30 years.

So, the arcs in the design set up this network of open spaces and public spaces that respond to the perimeter of the island and draw the river into this this new campus on the Southern tip of the island. The idea here was to think of this as a flexible framework that would accept change over time. The demographics of the place will change. The working environment will change, and there will be various players that will come in as the tech industry evolves in New York. So to create open spaces that would have definite legibility but not be preemptively over-programmed, was the task that would seed into its future. Each building has its own identity, but the floor of the campus really sets the tone for the development.

So, the arcs in the design set up this network of open spaces and public spaces that respond to the perimeter of the island and draw the river into this this new campus on the Southern tip of the island. The idea here was to think of this as a flexible framework that would accept change over time. The demographics of the place will change. The working environment will change, and there will be various players that will come in as the tech industry evolves in New York. So to create open spaces that would have definite legibility but not be preemptively over-programmed, was the task that would seed into its future. Each building has its own identity, but the floor of the campus really sets the tone for the development.

Here you can see the Weiss/Manfredi building, which is fronted by the legible signature of the campus in the landscape. A part of this was also thinking about how people who are not a part of the campus interacting with it. Do other Roosevelt Island residents come and use it to play, to look at the river, to be a part of it--even though they are not working in one of these fancy incubation spaces in the Bloomberg center. Innovation—that was the job of the campus landscape—to draw in people who would not otherwise participate in campus life, and to think of how modern campuses actually interact with the rest of the city.

The other big item in this in this project was looking at what sustainability means in the context of a new campus. Does it start with using some of the new technologies that become the signature of a tech campus? We came up with a self managing stormwater system where the stormwater in the cycle would be collected and treated onsite. Given the really tough conditions—this is a super windy and salt-blown site—it was important that the palette and the materials that we chose would create this robust and durable framework for a long future for the campus.

So the lessons learned here were that open space provides cohesion and supports a flexible framework over time. Sustainability is a huge part of creating responsible, smart places. Critical mass really matters for attracting density and making sure places are used. It is really important to concentrate activities in a smart way so that places become absorbed into the city’s fabric. Those are our big lessons from this project.

It is difficult to discern any attention to demographics and equity with such simplistic descriptions of lessons learned. Even if a project as given doesn't hand over the stakeholders, researching, finding and engaging them in some form is our responsibiltiy. -- J.B.

The second project I will speak to is in Newark, New Jersey. It’s a two mile stretch along the Passaic riverfront, It should really be the city’s front yard, but the Passaic is a Superfund site. The city perceives this river as a polluted waterway, which they have not had any incentive to access or use. Part of the task here was how do you change Newark’s relationship with its primary waterway. How do you bring it back into the people’s imagination as something that is healthy, that is usable, that is public? A part of this was really digging back, and trying to reclaim some inspiration from the Passaic’s ecological history as a recreational river, and as a water way for commerce and industry. It was a place that was a significant commercial trade post and there was great opportunity in finding inspiration in the tremendously rich cultural history of Newark.

Over its history, much of the lower portion of the Passaic River was used as a dumping ground for industrial waste (including the area of the river within the boundaries of the city of Newark), while its upper portion remained much less effected by such pollution. The lower Passaic has long been restricted from recreational activities such as swimming and fishing, but it has also been deemed less valued in terms of its rehabilitation for public use, due to the desire to maintain and "protect' its upper portion. Harrison resident, Robert Myers, couldn't recall anyone swimming in the lower river in nearly four decades, although he noted his father and grandfather did have memories of the river once being used by local residents for a swim. For more on the two "sides" of the Passaic, see "Passaic River's Two Faces: One Dirty, One Scenic" by Lena Williams︎︎︎ -- S.P.

These were all things that led us to be able to think about this two mile stretch in a nuanced way. We looked for cultural anchors and partnerships with institutions, so that we could really figure out the character and the program of each segment in a way that was relevant to every neighborhood. We really tried to address the needs of every neighborhood in a very nuanced way. As an example the area on the right side of the site, which is the Ironbound district, had a huge Portuguese population who loved the idea of playing volleyball on the beach. And one of the main programmatic ideas there was to create a large sand beach where there would be beach volleyball. We had only two sand volleyball courts and they came back to us and said, well, if you put three, we can have tournaments there. So we pushed a few things around and managed to create three volleyball courts, which was a really interesting back and forth process of learning from the immediate neighborhood. The other part of this was the outreach process we did hand-in-hand with the city. This is just a snapshot of some of the questions we asked them and got feedback on in terms of what programs people wanted to see on the river front, and what kind of river edge would people like to see. We asked all levels of detailed, high level programmatic questions, but also spatial questions in terms of what people’s desires were for this really polluted river.

What we were confronted with however, was the existing site, which is what you see on the left, and what everybody wanted was what you you see on the right. This wall, created by the Army Corps of Engineers, was something that we were not allowed to breach because the Passaic is polluted. Taking that wall away in the near future would have meant a tremendous tremendous hike in the budget of the project. So we had to work with this limitation of keeping this wall and yet creating this new riparian atmosphere that the community wanted, which is similar to what you see on the right. Given this limitation, we started drawing a few ideas of how to bring the river to the other side of the wall, if you will, without breaching it. We ended up designing a stepped garden space that runs along the edge of the park.

The effort was to reacquaint Newarkers with the possibility of a riparian ecology until the river does become available to them as a venue for recreation. Also, to remind them that this is possible at the edge of a river and that that rivers are a recreational and infrastructural entity that need to be leveraged. These were some of the various segments that we started carving out. This project is now under constructionto be completed next year. The major takeaways from this project were to create community, respond to the diversity that the neighborhoods present, and leverage this to creat difference in a large projects like this. Strategic investment-balancing high investment and low investment components- you always have a limited budget and there will be only vertain things you’ll be able to do really well. That was the idea behind saying there’ll be some elements of continuity that will run through the parking and create the fabric of the park. But there’ll be special elements that resond to the programmatic needs of the community. And the last was engage the water to the best of our abilities so that this polluted waterway can reenter the imagination of the population of Newark.

The next project I’ll speak about is Central green in Philadelphia. This was an interesting project in that it had very different issues than Newark and Cornell.

The next project I’ll speak about is Central green in Philadelphia. This was an interesting project in that it had very different issues than Newark and Cornell.

As designers, we need to be wary of depending on a programmatic checklist to fulfill social benefits. And how are community-driven program elements reconciled with "program" elements like pollution? -- J.B.

It didn’t have the density that most public spaces need to sustain themselves. The mission here was to create something legible that in the longterm would become absorbed in the fabric of the city, but in the short term would create a real icon, an attraction that would draw people to this area, which is rather far away from the center of the city. So the idea was to embed this iconic ring that serves as a framework of programs and still remains flexible for changing over time. So, if the demographics of the place change, if the attendance of the surrounding buildings—which was still TBD to a large extent—change, the park would adapt based on what the needs of the changing community are.

In the initial life of the park, we packed in a lot. There’s a track that if you run it five times, it’s a one mile loop. There are fitness areas, there are places to relax and places to sit and have performances. We gave it a checklist of programs that any developing neighborhood could take on and start using the park as a canvas for their programming.The idea was that eventually people would take over and start changing the park. It has already started happening, and the park is in its fourth year. People already started changing things around. One of these planting patterns has become a play area. Another one of them has been taken over as a stage. And so the incredible social interaction that we started seeing with this park was really something that we learned a lot from. The lessons learned in this for us was to create a legible icon, one that’s memorable and recognizable so that people are drawn to it. The second was to create a robust framework that can evolve with the neighborhood. And third, attractions—new neighborhoods need destinations, they need things to do and they also need to respond to changing demographics in a really flexible way.

Last one—Domino Park, which opened last year in the summer. When it opened, this stretch of post-industrial Williamsburg became available for public access in for the first time in 30 years. This used to be the site of the old Domino Sugar Factory, which was decommissioned in 1983.

The park is a component of a mega development of massive, massive buildings which will come up over the next few years. Therefore it was so essential to really build it first and get it right in some ways to present it to the community as an essential part of their new neighborhood. A lot of waterfront access projects tend to feel privatized and cut off from their neighborhoods because of the cul-de-sac mode of development.

To me, still to this day, the major thing that really created the publicness of this park was putting the street through the development that separates the private development from the public park, which preserves the publicness of it in perpetuity. The fact that it will never be a private backyard for all of the developments that will come up over the next 20 years. Expanding the minimum required public realm from just the thin sliver that most developers provide, to instead create and maximize the amount of public open space in this neighborhood was really important.

To me, still to this day, the major thing that really created the publicness of this park was putting the street through the development that separates the private development from the public park, which preserves the publicness of it in perpetuity. The fact that it will never be a private backyard for all of the developments that will come up over the next 20 years. Expanding the minimum required public realm from just the thin sliver that most developers provide, to instead create and maximize the amount of public open space in this neighborhood was really important.

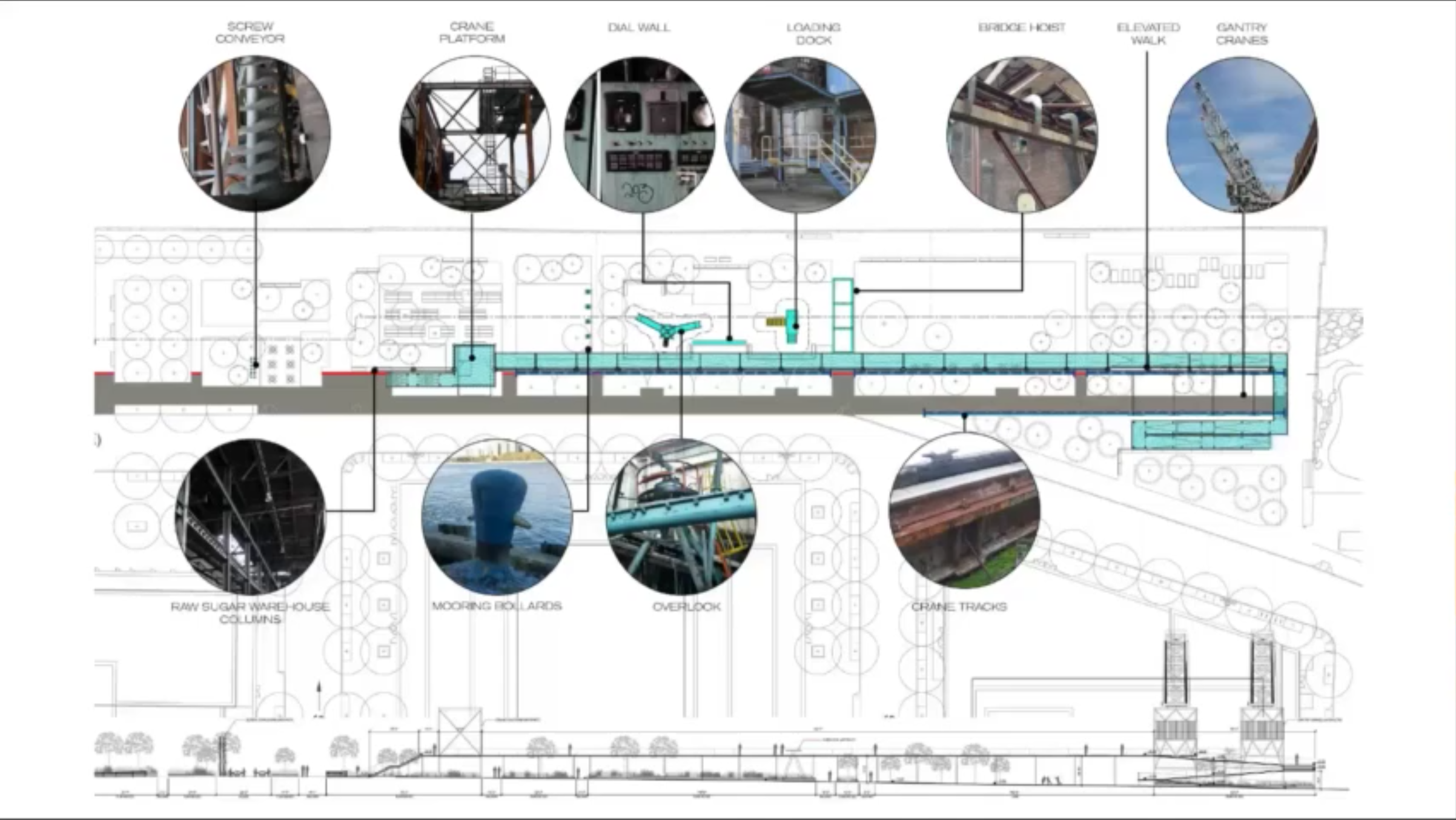

The programming of this park was also a product of a fairly sustained outreach program since this was going to be the first segment of Williamsburg that was going to open up in about 30 years. There was a huge demand for program in this area. Whoever is familiar with New York’s crazy zoning requirements—there are lots of issues like, you need 50% of planting, you can only have 50% of hardscape, you need to have “X” amount of benches. There were lots of rules and regulations that we had to play with it to get the right balance of maximizing program, but also still meeting the green requirements of the zoning code. The other really great aspect were the amazing artifacts that we found on the site. A lot of the sugar factory relics had been left, which we foraged and salvaged, tagged and put back. The structure that you see running along the side here was the raw sugar warehouse where Kara Walker did her beautiful installation just before it got demolished--the Sugar Sphinx. The whole idea of the park was to curate these pieces and absorb them in the experience of the park so that it would become a living history of that segment of the site’s history, which was a contentious one and needed some reckoning with. You can see how we found the site here, with all of the pieces and the relics that were left behind. These were moved around to create the various experiences of going through the gantry cranes, walking through the elevated walk, and having the park beneath. The Domino Sugar refinery is the centerpiece of the site and it’s the only building that has been preserved as a part of the whole park.

This is the artifact map of all of the stuff that we found in the park and how that becomes a museum of elements on the street side of the park. Here are a few images showing how we built the the artifact walk, and some of the great images from inside the factory before it was demolished. What has been really interesting is the diversity we have observed in the way this park has been been occupied. You couldn’t believe the number of people who showed up who don’t even live in this neighborhood. Right now it’s suffering a little bit from the “amusement park” complex, which we hope will become more neighborhood oriented as time progresses.

But the large variety of uses and programs really draws in a diverse demographic into this park. There’s elements for almost everybody to come and be at this park, even if you’re not a resident of the neighborhood- even dogs. Thanks to social media, how the park is used as become really visible. We can start seeing patterns of use in terms of which parts of the park people use more, how they are used during different times of the day. I don’t think any other park from our office has been documented so much on Instagram yet, other than the Highline.We are hoping to learn more in terms of how places like this are used for social media.

Lessons learned from this: it was really valuable of this development to build a park before any buildings. It really communicated an investment in the neighborhood and it immediately built a positive relationship with the neighborhood. The power of the street—as I mentioned before, the fact that it was a threshold between the most public part of the park, and what will be a private part of the development. It really deepened the sense of publicness of the place and heightened the sense of waterfront access. And lastly, the super vibrant and very diverse mix of uses, which was really in response to the community demands and that makes it makes it a fun attraction to go to. That’s it. Thank you.

Lessons learned from this: it was really valuable of this development to build a park before any buildings. It really communicated an investment in the neighborhood and it immediately built a positive relationship with the neighborhood. The power of the street—as I mentioned before, the fact that it was a threshold between the most public part of the park, and what will be a private part of the development. It really deepened the sense of publicness of the place and heightened the sense of waterfront access. And lastly, the super vibrant and very diverse mix of uses, which was really in response to the community demands and that makes it makes it a fun attraction to go to. That’s it. Thank you.

Social Media Parks. Is that a new aspiration?

Does popularity equal diversity? There is something to be said about observing the use of a park as ultimately it is difficult to predict its use, by whom. Some urban wilds parks (eg, the well known German parks Sudgelande Nature Park, Templehof Park, etc) are proving to be attractive to some "alternative" cultures, but that emerges from the landscape not being overly designed nor heavily programmed. -- J.B.

Does popularity equal diversity? There is something to be said about observing the use of a park as ultimately it is difficult to predict its use, by whom. Some urban wilds parks (eg, the well known German parks Sudgelande Nature Park, Templehof Park, etc) are proving to be attractive to some "alternative" cultures, but that emerges from the landscape not being overly designed nor heavily programmed. -- J.B.