LANDSCAPE PERSPECTIVES: EQUITY IN + BY DESIGN: GINA FORD

BENJAMIN C. HOWLAND PANEL 2019

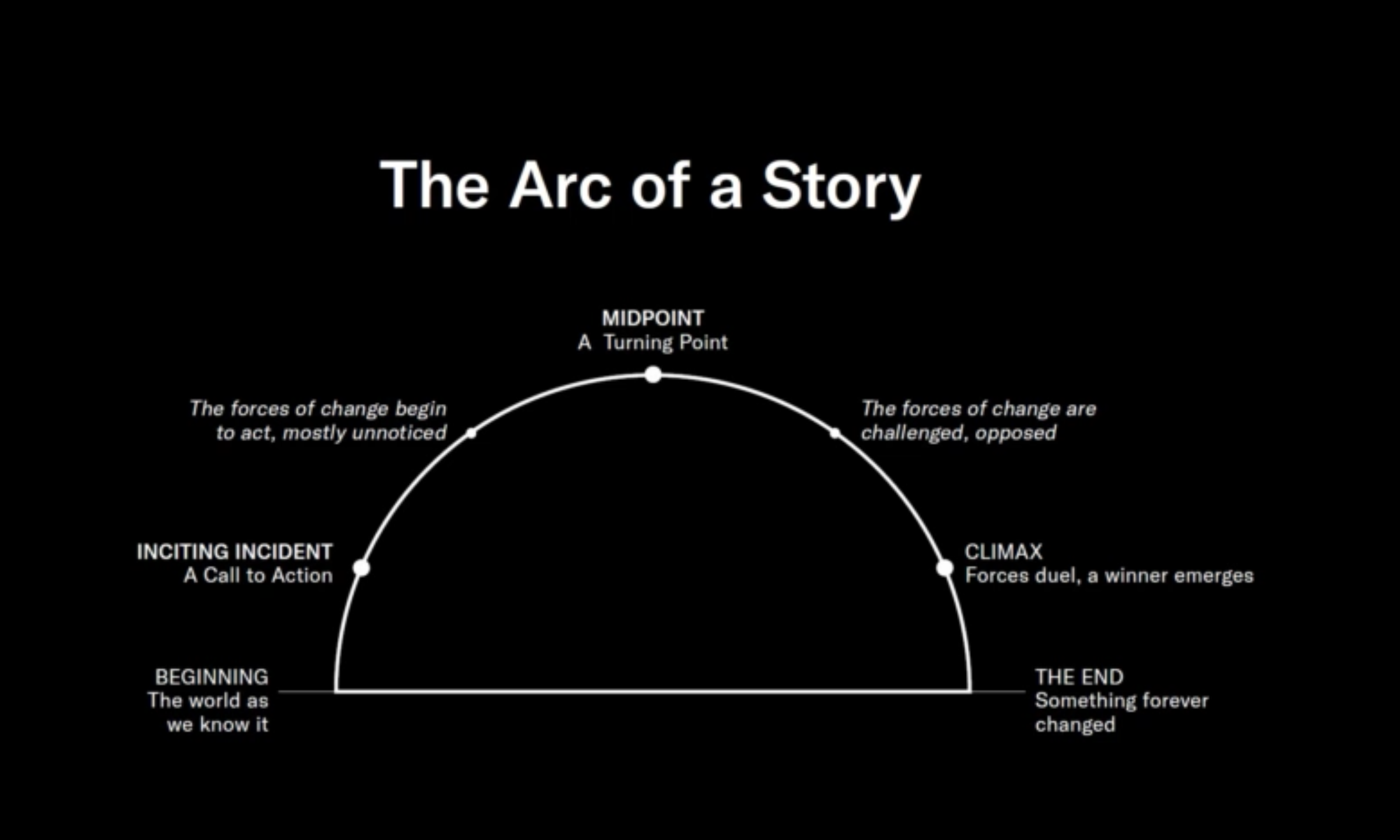

We often use this metaphor with our teams and with the communities we work with, that master planning and design is really about writing a story together. In every case there’s context that exists before the story starts. There’s some inciting incidents and need for change that’s brought to the fore. Those forces start to actually work on everybody in a way that might go unnoticed for a while until it rises to a point where something shifts. It’s really a beautiful moment in a project where there’s this shift and everyone gets a sense of it, but then it gets actualized and operationalized through the conclusion of a project. And ideally in the end there’s a winner— there’s a winning idea, there’s a winning future, and something has fundamentally been changed forever in that process. I think it’s a really beautiful way to think about projects. So I’m going to show you three stories, three really short stories, and talk about how the shift happens and how we think about this. In practice, so much of what we do at Agency, and what I’ve done in my life doing public work, is trying to find the way of writing stories with lots of different kinds of people, people with different language abilities, people with different ages, genders, race—how do you ask the questions? How do you invite the answers? How do you invite a two way dialogue? This is a cross section of some of the projects we’ve been working on the last year where this idea of writing the story with the community is so central. And importantly, how do you get the right people to the table, or the people to the table that really need to be a part of writing that story? And then, how do you hear their voices and translate that into a design strategy?

Three examples of this idea of community story writing: one, Rebuild By Design, The New Jersey Shore; the Miller Prize, a project we’re right in the middle of right now in our studio; and then one personal story about my own change in the last few years. First I’ll start with Rebuild By Design, which was a competition. Ten teams were selected to look at the New York area post Hurricane Sandy by the US department of Housing and Urban Development, HUD. It was an amazing competition. I’ll just show you a few slides from it. This for me was a really game changing project in the way I thought about what was possible in practice. Brie, my now business partner and I led this while we were at Sasaki Principles. Our team chose to look at the New Jersey shore as our case study for the rebuild work because it’s such an important iconic, memorable landscape. It’s also a huge economic driver for the state. And it was devastated by the storm as we know. And so this was a really interesting place where all of these small communities could think about what resiliency meant. So the storms came through and had different impacts on different communities throughout the shore. But what was most profound was the impact on the people of the shore and the culture and how that started changing, as well as the economy and how that started changing as well. The point of this story is really to say we came at this being landscape architects, very excited about the whole idea of dunes and the beach front.

Ford exemplifies the generation when communities were moving away from being relatively silient clients to becoming vocal collaborators. Coverting stakeholders into engaged participants obviously takes an enormous amount of time, patience, empathy. Brava to those firms that are finding the fruit of that labor. -- J.B.

So that top image is the Asbury Park boardwalk, a small community in the North side of the Jersey shore, made famous by Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band. This is where they performed--E Street is in Asbury--which is also the place where Tony Soprano goes in his dreams, if you guys are Sopranos fan--very deep in New Jersey lore. We came thinking, this is all about building dunes and establishing kind of an armored edge in this community to protect it from the sea. And in talking to the community, we found out it was a very different corridor. It was actually one of the East-West corridors that led from the beach to the other side of the tracks where the African American population was sort of segregated in the community. Importantly, and we didn’t know this going in, but Asbury Park was one of the last beaches to be integrated and there was a long historic pain of that loss and separation from the beach landscape. It was very much given that the white population lived by the beachfront and the black population lived on the other side of the tracks.

When we asked the community what key to their resilience was, that was the issue they wanted to tackle. They were less afraid of the sea. They were more concerned about building bonds together. So as part of our strategy, as part of our community outreach, we staged a parade that went from that west side of the community to the ocean front, brought the community together in the neighborhood west of the train tracks, the African American part of town. We started a conversation about what resiliency looked like there and then March together from the neighborhood to the beach front. In a way, this was symbolically acknowledging the disconnect and that future resilience really meant togetherness. All parts of the community participated in this parade. It was educational. There were stops along the way talking about resiliency, and we had the school marching band participate as well.

The parade is a great example of design empathetic thinking in action- connected to the community in planning, participation and after influences. It is an excellent way to change the conversations between designer and client.-- E.C.

An examination of history of Asbury Park highlights the emerging Jim Crow character of the Jersey shore following Reconstruction where the tensions between contested notions of political, social and economic equality within the public realm are well-documented through the press (including The Asbury Park Press, The Daily Journal, and the Shore Press). In just one example, The Daily Journal's article "Too Many Colored People" (published July 17, 1885) did not represent an objection by white northerners to the political or legal enfranchisement of black Americans, but rather to the social intermingling of black citizens in the public spaces of white patrons. By 1887, all African Americans, both those who worked at as well as those who wished to vacation in Asbury Park, were restricted from its beaches and other public facilities, such as bathing houses, pavilions and promenades. The African American community organized continuous rallies, demonstrations and public meetings, speaking out about the moral and social responsibility of the town to allow free and uninterrupted integration.

For details on the emergence of segregation in Asbury Park, see "Greetings from Jim Crow, New Jersey: Contesting the Meaning and Abandonment of Reconstruction in the Public and Commercial Spaces of Asbury Park, 1880-1980" by David Goldberg (2006)︎︎︎ --S.P.

Time plays an important role in the relationship between a consultant and a the community. By recognizing the temporary role within that community, the designer can value the role of process. As a new designer, I am continually reminded that the role of the planner/designer is to support the community and client in their goals. Many panelists discuss the importance of listening and re-routing the mission to align with community needs. -- L.G.

As we moved into our design phase, it really got us to think--this is Asbury Park looking from the ocean back towards the community that yes, it’s still about this boardwalk edge and making sure that that’s resilient to the oncoming sea during storm surge. But importantly, as we learned from the community, it’s also about these really important connectors and this idea of making the landscape of the streetscape unifying rather than dividing. So both in terms of the streets that connected those neighborhoods and also the lakes and the water systems, everything started being about that kind of movement east to west- really acknowledging and honoring that.

This project illustrates an approach to the important work ahead of us as we work to design spaces for climate justice. As designers in the age of climate crisis, we must constantly ask: How do we ensure that our projects resist the human urge to put up barriers/walls out of fear, and instead create connections through shared experiences in spaces that help us address past trauma while building our shared capacity to support one another? The act of parading is collaborative, performative, often habitual, and is employed to honor both happy and sad events through cultural expression, so it is a brilliant way to to cultivate a sense of collective strength. Recommended related reading ︎︎︎ -- B.B.W.

We made sure as we moved down to the beach front, that transforming that boardwalk did what we wanted from the start--ecological improvement, more habitat, more dune protection, and accumulation of sand over time--but also that it was a social setting that really was welcoming and inclusive for all in all the ways we could imagine that might mean. Why I tell this story isn’t so much because I love the design work. I tell this story because as part of this process, the committee that we worked with in town, the volunteer committee that actually helped organize the parade got so enchanted with this idea of resilience that it ran for all city commission seats and the mayoral seat the year after we left town, and they won. They have been running the community on this idea of resilience. So the parade goes on without us. I think that’s the really extraordinary story that we can tell of this is: that by building systems of capacity by engaging the community around those core issues, it really motivated something primal in them to then take this on and lead it on without us, which to us, is really an achievement beyond achievements.

Here's a case where community rewrote the brief, or should it be said that the landscape architects rewrote the brief for the community. The former is stronger; it's the reason why the parade went on without the designers. Someday just that catalytic act will win a design competition. -- J.B.

That was story one. That’s my past life. So now I’m going to tell you a story about my current life. This is a project we’re right in the middle of, it’s called the Miller Prize in Columbus, Indiana. Do you guys know Columbus, Indiana? Anybody? Okay. Do you know [Dan] Kiley’s Miller Garden? Okay. The Miller Garden is in Columbus, it’s a modernist Mecca. It’s a city of real architectural treasures. As part of its preservation agenda, the city started a program a few years ago where it invites young up-and-coming firms--I’m not really a young firm, let’s say up-and-coming firms, new firms--to do these temporary tactical installations over the course of a year. You’re given the year and a budget, and then in August you’re supposed to make something that the community engages with.

So we’re thrilled to be the first landscape firm that has been given this honor. Did someone just applaud or drop something? Yeah, we can applaud! I have a chip on my shoulder cause I’m like, oh, we’re the first landscape architects we’re going to do something really landscape-y. Anyway, we’re the first landscape architects to get this prize. And we were given this really extraordinary site.

So we’re thrilled to be the first landscape firm that has been given this honor. Did someone just applaud or drop something? Yeah, we can applaud! I have a chip on my shoulder cause I’m like, oh, we’re the first landscape architects we’re going to do something really landscape-y. Anyway, we’re the first landscape architects to get this prize. And we were given this really extraordinary site.

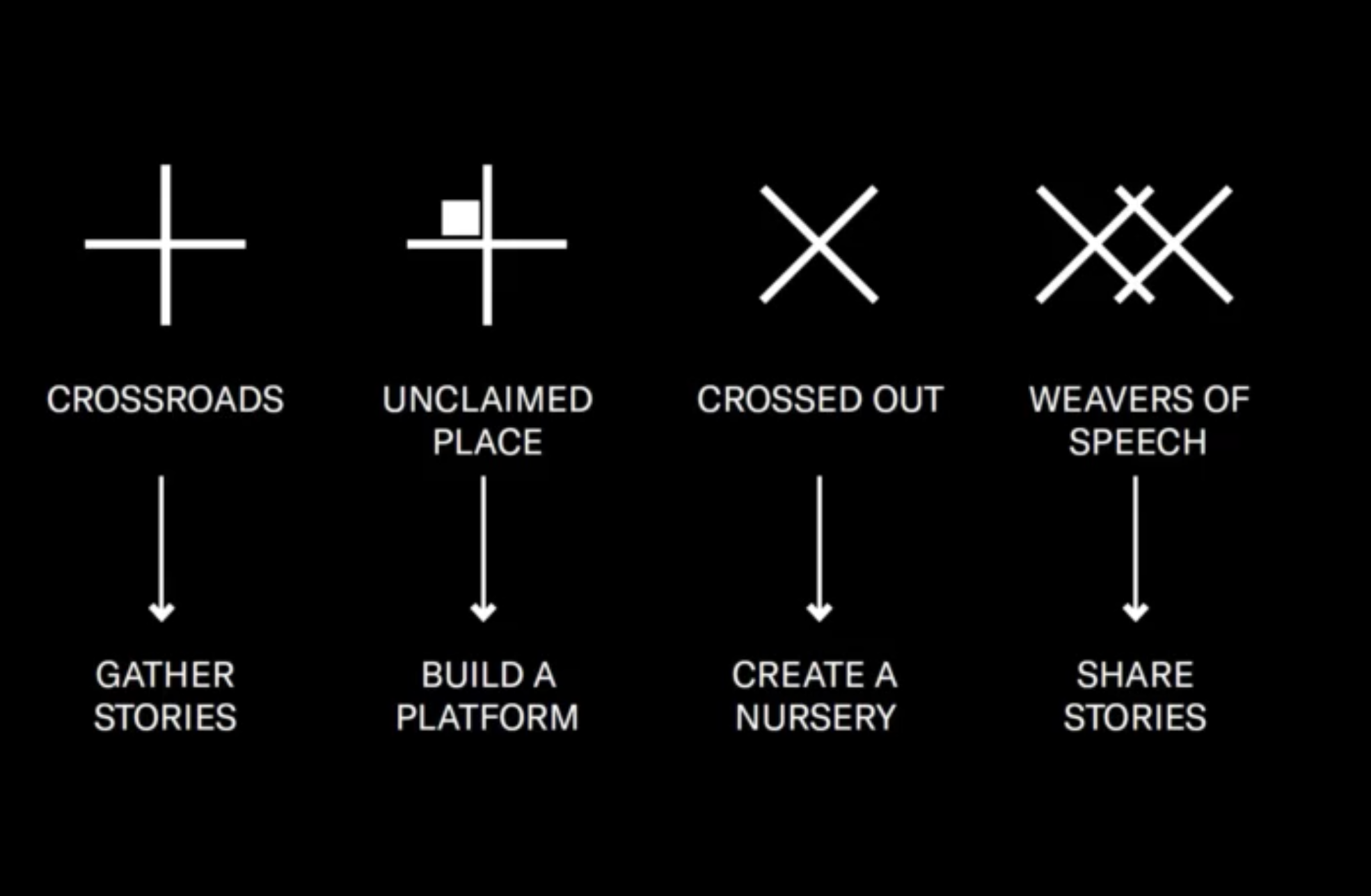

So you’re given a site that you have to work with, which is Paul Kennan’s AT&T building and old switching facility. In the old days, it used to be a fun place where the phone lines were connected from switchboard from one to another. Paul Kennan, the architect, unified the whole block, which was a series of fragmented utility buildings, by making this ‘machine in the garden’ building, with this trellis and this mirrored facade and by our visit, really tough sidewalk. So that was our given site, which was interesting--and Jha D knows this because Sasaki is doing it too. You guys were given a big lawn and we were given this little brick sidewalk, no man’s land. So it’s okay! MASS Design is also doing a Miller Prize installation. Our observations of the site became our driver for how to think about this installation. We described it as this series of existing conditions: that it’s at a crossroads, that there are elements that been crossed out, that it’s an unclaimed place, and that it’s home to what we called the “weavers of speech”.

I’ll show you what that means and how we translate that. Here’s the building again and all of its foggy glory. It sits at a crossroads and what we call a “zipper zone” between the neighborhood fabric and the downtown core. It’s abutted by a bunch of social services and institutions: a Presbyterian church, an old folk’s home, and a shelter for battered women surround our building. So, we have an interesting constituency and it’s about a block off of the main street. It’s at this edge condition between these more solid conditions. It’s been crossed out--this is a really grainy picture, I apologize. It’s one of the only great photos we’ve been able to find of a condition that’s since been removed.

Kennan’s architecture had this white trellis that almost came to the ground, with vines growing up it. So the building, which you saw already, in Kennan’s vision dematerialized because it had this green facade on one side. So it became this kind of mystical, magical land. It became a bird problem. In later years, this happens to landscapes and buildings. They unceremoniously came one day, cut down all the vines and removed two thirds of the trellis. So now we have this building that you all saw, this sort of barren machine without its white trellis and without it’s purple flowers--wisteria. It would have bloomed this incredible purple. It’s also, because of that, in a lot of ways a really unclaimed space. It’s not loved because it doesn’t have an identity anymore. You see the barren white trellis that used to hold these vines and the planter beds that used to hold them now planted which junipers. The community is trying to plant these little cherry trees as a way of regreening and making this sidewalk hospitable again, but it’s really an unclaimed place that we thought could be claimed through this work.

And then lastly, we were just totally amazed by this idea that this building used to be the place where women in Columbus probably had some of their first jobs across the country. Women became the switchboard operators. It was one of the first legitimate professions for women. This notion that women were in there, in that building connecting people through conversation was such a beautiful thing. Also, the idea that that system is now obsolete and those women are gone and much like the trellis and much like the purple flowers, they too have been erased from the site in a lot of ways. We likened that in our minds as we thought about recent controversies in architecture and architectural practice about the systematic erasure of women and their contributions in the design profession. We were talking about this today at lunch--most famously, Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi. But you can look at many partnerships over the years where slowly, the woman’s name gets taken out of the equation. We were particularly thrilled because this prize is named not just for J Irwin Miller who was sort of the patriarch of Columbus, but also Xenia S. Miller, his wife, who also was a powerful character. In a lot of ways, we wanted our project to recall the purple flowers, the white trellis, and the women who were systematically erased, and bring them back to activate and claim this space.

For each of those notions, we then developed a physical strategy for ‘crossroads.’ We asked ourselves: how do we bring together diverse constituencies and gather stories to undo the unclaimed space. We wanted to build a platform, a changeable landscape that really invites people to use it in a new way, and create a nursery to start bringing back some of the green that was removed. Lastly, we wanted to share stories to really bring back some of the stories that weren’t getting the marquis treatment.

For each of those notions, we then developed a physical strategy for ‘crossroads.’ We asked ourselves: how do we bring together diverse constituencies and gather stories to undo the unclaimed space. We wanted to build a platform, a changeable landscape that really invites people to use it in a new way, and create a nursery to start bringing back some of the green that was removed. Lastly, we wanted to share stories to really bring back some of the stories that weren’t getting the marquis treatment.

In her 1989 essay, "Room at the Top? Sexism and the Star System in Architecture”, Denise Scott Brown recounts countless examples of exclusion and discrimination as a female architect. Only a few years later in 1991, when Venturi Scott Brown was selected for the highly noted Pritzker Prize, only Robert Venturi was recognized and honored. In 2013, two students at Harvard's Graduate School of Design mobilized an online petition that obtained over 20,000 signatures in demand of Scott Brown's recognition by the Pritzker jury. In response, Scott Brown noted, "They owe me not a Pritzker Prize, but a[n]...inclusion ceremony. Let's salute the notion of joint creativity." Lord Peter Palumbo, chair of the Prize, thanked the petitioners for calling attention to the problem, but noted that "a later jury cannot reopen, or second-guess, the work of an earlier jury." For more information about what Gina Ford aptly described during the Howland Panel as "the systematic erasure of women and their contributions in the design profession," see the article, "Snubbed, cheated, erased: the scandal of architecture's invisible women" by Oliver Wainwright, published on October 16, 2018 in The Guardian.︎︎︎ -- S.P.

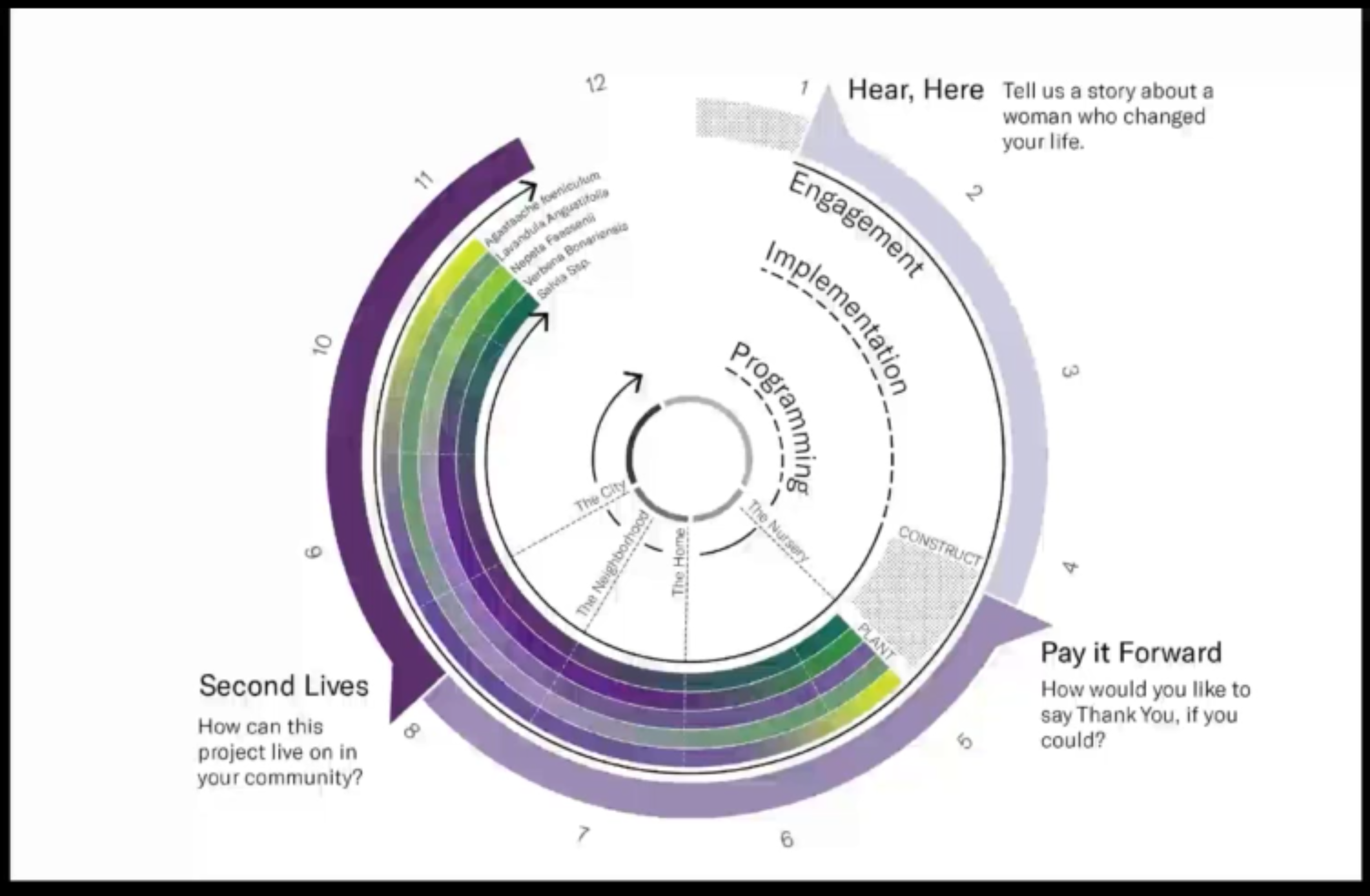

So first, as we think about gathering stories--very unlike the Miller prize, and I think this is part of being a landscape architect and a public realm designer--we decided that we weren’t going to wait until August and then open some object up (not that that’s what they asked us to do, but that’s what people tend to do). We wanted to start our process in January with an outreach campaign. We started distributing these cards all around town, at the library, at all of the, um, sort of social service places at all of our community meetings, with our logo on them--”XX”-- meant to evoke the weavers of speech, asking the community to tell us about women that had changed their life.

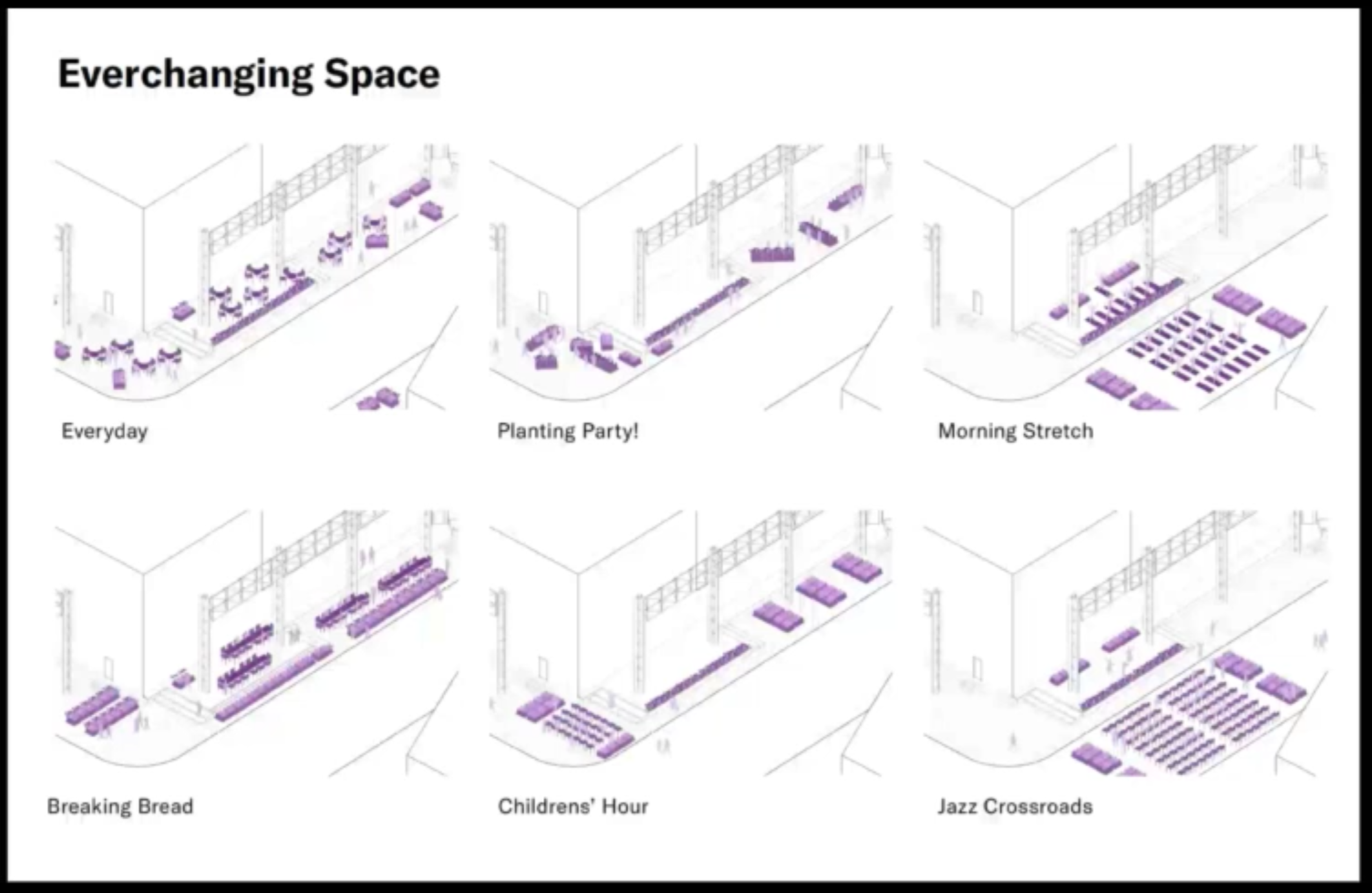

We’ve been collecting these stories over the last few months and beginning to catalog the ways in which women have enacted change in this particular community. That was part one, that we started in January and this is ongoing now. We’re just finishing our listening and question campaign now. Secondly, we’re in the process of building the platform. Rather than a singular platform we’ve decided to build something that’s infinitely customizable--that’s a reference to the truss system that was removed. We’re working with a truss manufacturer to make these truss pieces that can be assembled in lots of different ways so that we can continually, over the course of the coming months, change the configuration and host a whole series of different kinds of events and programs in the landscape. It’s meant to be a low cost, simple way of actually changing the site over time--whether as seating or platform or stage.

We’ve been collecting these stories over the last few months and beginning to catalog the ways in which women have enacted change in this particular community. That was part one, that we started in January and this is ongoing now. We’re just finishing our listening and question campaign now. Secondly, we’re in the process of building the platform. Rather than a singular platform we’ve decided to build something that’s infinitely customizable--that’s a reference to the truss system that was removed. We’re working with a truss manufacturer to make these truss pieces that can be assembled in lots of different ways so that we can continually, over the course of the coming months, change the configuration and host a whole series of different kinds of events and programs in the landscape. It’s meant to be a low cost, simple way of actually changing the site over time--whether as seating or platform or stage.

The brilliance of the logo, and dissemination of the cards all over Columbus reads as a powerful introduction to inclusive design- an invitation to the importance of the human experience to change built form. --E.C.

We’re going to create a nursery at the same time that we’re building the trusses. We’re partaking in a community planting program, as MASS Design is. We’re doing a temporary purple flower landscape of flowers that will be comfortable on this hot dry site of the sidewalk that we’ve been given. Plants that evoke a kitchen garden have a sort of domestic quality to them that can really survive and flower all summer; ones that we imagine at the end of summer people might want to take and plant in their gardens so that they can distribute themselves as a temporary installation. Everything we’re doing has to be either decommissioned or given away. And so the idea that the community can both help us plant, but then also take the plants with them is part of the notion.

And then lastly, after we build this landscape, which is happening in a month, over the end of May and beginning of June 2019, then we begin a series of story sharing opportunities. These are all thematic and based on the gathering of stories from the community. And we don’t know exactly what those are yet. We’re in the process of tallying them--but we started imagining the kinds of things that we could see here using our infinitely changeable pieces at play. We imagine that all of these things will really be a celebration of women. So I don’t really know what they’re going to be yet. I wish I could tell you. I do know that we’ve heard a lot about education, so there’ll be something around that theme. We’ve heard a lot about famous politicians that were women, powerful leaders on the national stage.

Those are the kinds of things we’re starting to murmur about as we plan these events. But the beautiful thing is, is that we’re trying to also showcase in addition to the stories about women, this notion that the landscape is something that’s constantly changing and ever changing in its configuration. Breaking out of this idea of the singular moment of an architectural unveiling, it’s instead a making of the site that happens over many months, that flowers for many months and then becomes decommissioned over many months. So we’re showing that landscape is not something that’s confined to a day, that it’s really about a season of occupation and all the way kind of telling this idea about telling stories.

“Landscapes do not lie; they are the embodiment of all that we do on Earth.”

“More cities boast integrated systems of parks, open spaces, and greenways, providing evidence that nature can return to the urban scene and enhance communities in biological and socioeconomic ways.”

-Nature and Cities: The Ecological Imperative in Urban Design and Planning︎︎︎ -- Y.C.“More cities boast integrated systems of parks, open spaces, and greenways, providing evidence that nature can return to the urban scene and enhance communities in biological and socioeconomic ways.”

Agency's Miller Prize project seems more about cultural values than social issues. That said, there was more room for an expose, a critique to further unclad the once perfect modern object. Landscape design schemes so often placate. In the case of a temporary installation, there may be room to kill 'em with kindness. -- J.B.

Okay. Last story. So the last story is the personal one. The last story is the one about my story about where the incident happened and the change happened and then the world was forever changed. And that’s because up until the end of last year, 2017, I was at Sasaki Associates for 21 years, a great practice and a great firm. I was one of the first woman principals in that practice and was a principal there for 10 years. Did a tremendous amount of work there. Some of it you might know, and really led a lot of public landscape making and community engagement with my now partner Brie Hensold. And then, you know, the incident happened and the incident was really a lot of different things that happened over the course of 2016. I saw Hamilton, it was kind of life changing. I also saw Beyonce’s “Lemonade”--equally life-changing. You can’t see those things and then go back to normal life: story changed forever. The Women’s March, the national election and the toll that took on a lot of us that were really excited about a female president and that female president in particular, was just a really hard, challenging moment. I think it continues to be for many of us who believe in women’s rights and people’s rights in this country. Lastly, I’d say the Landscape Declaration Summit in Philadelphia was a really nice moment to reflect on the state of the profession. I was one of the speakers and got to speak about these ideas of resiliency and collaboration. I didn’t realize it at that moment, but talking at the LAF (Landscape Architecture Foundation) was starting to define this future practice in words, that I would ultimately go on to do.

And so, 2016 happened and I started planning for my own story to change and founded this new practice called Agency Landscape and Planning--really founded on this idea that agency is about our ability to change our stories, and to write our own stories, and to write the story we want to live in, rather than the story that we’re told or given. So it’s all about this idea of celebrating the optimism and potential of design and planning to really transform the world and make positive change. I started this with my business partner Brie. She’s an urban planner and she also was a principal at Sasaki. So we Thelma and Louise’d it and held hands and drove over the cliff together. Haven’t regretted it a day since we did it. It’s been amazing and tough and wonderful and I’m just so grateful for her and her big smart brain and her quiet way. I’m the extrovert. She’s the introvert. Anyway, it takes all kinds. This is typically a changing GIF, which is our “A”, which is our logo, which changes through many A’s, but it’s not working because it’s on my computer. So I apologize about that. But you get the idea, we’re all about this idea of many different things, many different voices, many different forms of beauty and we love celebrating this notion of new forms of collaboration that we’re not bound anymore. We can collaborate in so many different ways and there’s so much joy and pleasire in doing that, which we celebrate on our website, on a page called collaboration. When you are a woman and you leave a big practice to start your own practice, everyone goes, “Oh, you’re gonna do a little local, a little Boston?” And you go, “No, no, no, I’m gonna do big national.” “Is it because you want to spend more time with your family? Is that what-” “No, no, I like my family. But I’m, I’m on the road and am doing this.” So we are living the dream. We are working all over the country. These are the projects we have on the boards right now. An extraordinary amount and array of work, all public sector, all dedicated to these issues that are really central to our practice. So I showed you a project about equity and an existing community, a project about feminism and space as idea. And then lastly, in our own practice, we see ourselves as advocates and recently, and if anyone follows us on Instagram, you know, we’re really advocating for change in the workplace for more gender equality at the top of our lungs anywhere we can.

And so, 2016 happened and I started planning for my own story to change and founded this new practice called Agency Landscape and Planning--really founded on this idea that agency is about our ability to change our stories, and to write our own stories, and to write the story we want to live in, rather than the story that we’re told or given. So it’s all about this idea of celebrating the optimism and potential of design and planning to really transform the world and make positive change. I started this with my business partner Brie. She’s an urban planner and she also was a principal at Sasaki. So we Thelma and Louise’d it and held hands and drove over the cliff together. Haven’t regretted it a day since we did it. It’s been amazing and tough and wonderful and I’m just so grateful for her and her big smart brain and her quiet way. I’m the extrovert. She’s the introvert. Anyway, it takes all kinds. This is typically a changing GIF, which is our “A”, which is our logo, which changes through many A’s, but it’s not working because it’s on my computer. So I apologize about that. But you get the idea, we’re all about this idea of many different things, many different voices, many different forms of beauty and we love celebrating this notion of new forms of collaboration that we’re not bound anymore. We can collaborate in so many different ways and there’s so much joy and pleasire in doing that, which we celebrate on our website, on a page called collaboration. When you are a woman and you leave a big practice to start your own practice, everyone goes, “Oh, you’re gonna do a little local, a little Boston?” And you go, “No, no, no, I’m gonna do big national.” “Is it because you want to spend more time with your family? Is that what-” “No, no, I like my family. But I’m, I’m on the road and am doing this.” So we are living the dream. We are working all over the country. These are the projects we have on the boards right now. An extraordinary amount and array of work, all public sector, all dedicated to these issues that are really central to our practice. So I showed you a project about equity and an existing community, a project about feminism and space as idea. And then lastly, in our own practice, we see ourselves as advocates and recently, and if anyone follows us on Instagram, you know, we’re really advocating for change in the workplace for more gender equality at the top of our lungs anywhere we can.

I had the great pleasure of doing a panel about this issue at the ASLA Conference in Philadelphia with this incredible cast of characters shown here, all women who left really high profile, big firms like West8, SWA, Sasaki, and Design Workshop in the last two years to start their own practice. No coincidence of that right? We have to take charge of our destiny. And the four of us with Steven Spears, who was our moderator, collectively wrote this resolution which lives on change.org. It’s a commitment to our own practices demonstrating workplace equality, and we’ve asked other firms to post it, to share it, and to sign it. So please, I invite you all to sign it. In conjunction with that and this month’s Landscape Architecture Magazine, we have an article about those four intertwined stories of starting a new business and what that’s looked like for us.

So it’s again, another form of advocacy to make known some of the challenges we experienced in the workplace. As wonderful as our workplaces where in some ways they just didn’t live up to some of our expectations, and we wanted to say this is what it looked like. This is what we’re trying to make now. And then lastly, as part of that, we have this campaign all month on Instagram called w_x_la, where we’re celebrating other women led practices that have come into being in the last few years, and some of the pioneers who really paved the road for women in practice. Within the grid of the Instagram feed, there’s feedback that we’re receiving about the article, some of the things that are negative, some things that are positive, but really just putting it out there so everyone can see what we’re learning as we’re going through this process. So that was the last story. That’s my own personal change and kind of where my practice is headed. And again, I’m humbled to be here and grateful and very excited to hear these incredible women talk after me. Thank you.

To be an advocate for equity for herself and her colleagues is highly admirable. That, I mean she, is the embodiment of equity. For myself and other professional and academic colleagues, there is another type of commitment to being a slow burn role model and mentor. Bottom line is to raise hell. -- J.B.

The SAM list and #metoo have shaped new scrutiny of the problems of the architecture and design professions.

Equity by Design︎︎︎ is a great resource for understanding racism and sexism within the design professions in the US.

See also Despina Stratigakos, Where are the Women Architects?︎︎︎ and Brown,Harriss, Morrow, and Soane, eds, A Gendered Profession: The Question of Representation in Space Making︎︎︎.

Beyond representation and everyday sexism and racism, there is also the question, as with architectural education, of how we conceptualize and organize professional practice. --J.S.

Equity by Design︎︎︎ is a great resource for understanding racism and sexism within the design professions in the US.

See also Despina Stratigakos, Where are the Women Architects?︎︎︎ and Brown,Harriss, Morrow, and Soane, eds, A Gendered Profession: The Question of Representation in Space Making︎︎︎.

Beyond representation and everyday sexism and racism, there is also the question, as with architectural education, of how we conceptualize and organize professional practice. --J.S.