LANDSCAPE PERSPECTIVES: EQUITY IN + BY DESIGN

MAURA ROCKCASTLE

BENJAMIN C. HOWLAND PANEL 2019

Below is an annotated transcript of Maura Rockcastle’s lecture for the 2019’s Benjamin C. Howland Panel. Thank you to the UVA faculty and students that sent annotations and comments. Initial key for annotators can be found on the lower navigation panel.

I’m going to talk a little bit about where we began at TEN x TEN. We’re four years old, almost to the week. I’m going to talk specifically about where we begin when we think about equity; about the design process itself and doing work that has meaningful impact; about how we believe we are trying to rethink that. And then I’ll dive into two projects.

So we start with questions. This quote by Kyna Leski in her book, The Storm of Creativity is one that particularly resonates for us. Questions have remarkable power to undo preconceived choices, disrupt assumptions, and turn your attention away from the familiar. All of these lead to a more open mind.The creative process comes from displacing, disturbing and destabilizing what you think you know. We’re agitated when we discover we don’t know, and that compels us to go forward in search of knowing. So we questioned for the sake of the process. A creative process that emerges from not knowing is authentic and can be highly responsive to the different places that we’re working, which is important to what we’re here to discuss today.

We question to confirm what a project is or should be about. We ask how to do a project right. Not necessarily ‘what is the client looking for?’ This approach isn’t easy. It takes time and it’s risky, especially for a very small office like ours with very little resources. And unfortunately sometimes what is right and what the client is looking for are in opposition. So that means we invest time in things we believe in, but we don’t always get paid for it. So this is how we begin and how we’re committing to a practice that takes issues of equity seriously and tries to understand the challenges of any given place or community or story.

So we start with questions. This quote by Kyna Leski in her book, The Storm of Creativity is one that particularly resonates for us. Questions have remarkable power to undo preconceived choices, disrupt assumptions, and turn your attention away from the familiar. All of these lead to a more open mind.The creative process comes from displacing, disturbing and destabilizing what you think you know. We’re agitated when we discover we don’t know, and that compels us to go forward in search of knowing. So we questioned for the sake of the process. A creative process that emerges from not knowing is authentic and can be highly responsive to the different places that we’re working, which is important to what we’re here to discuss today.

We question to confirm what a project is or should be about. We ask how to do a project right. Not necessarily ‘what is the client looking for?’ This approach isn’t easy. It takes time and it’s risky, especially for a very small office like ours with very little resources. And unfortunately sometimes what is right and what the client is looking for are in opposition. So that means we invest time in things we believe in, but we don’t always get paid for it. So this is how we begin and how we’re committing to a practice that takes issues of equity seriously and tries to understand the challenges of any given place or community or story.

This focus on questions and questioning reflects an equitable approach to design right off the bat. It means you need to have humility, curiosity and empathy to begin to listen to the answers. --J.B.

We ask questions like ‘What has made these landscapes or communities what they are? What is embedded here that we can no longer see? What is the client asking for? Is that right? Is that what the community needs or wants?’ So to ask these kinds of questions over and over again for us as a way of committing to an open and more perceptive worldview, one that is hyper aware of our surroundings. We want to be a practice that is nimble and dynamic, that pays attention and does the research and practice, that is intentional about who our collaborators are and who we’re bringing to the table to do this work with. And that disrupts when it needs to. We’re still building up the confidence to do that in a successful way. But it’s our responsibility to remain open, to actively listen, to amplify culture and to reveal truth.

Many of our projects exist within the margins of urban areas in former industrial sites on sacred indigenous sites and reservations and marginalized neighborhoods and segregated cities like Omaha and Detroit, Milwaukee, St Louis and Minneapolis. The way our city Minneapolis, in particular, has changed over time is a huge undercurrent that affects which projects we’re pursuing, which clients we’re seeking relationships with, which clients we feel comfortable challenging, who our design partners are, and how we approach community participation in different parts of the city– two cities, St Paul also – I won’t ignore them. Focusing on the physical perceived and dynamic issues of our time or actively trying to change how our way of working and designing is actually addressing these issues.

How we work is also a strategic choice. Ross Altheimer, who many of you know, is a UVA alum and my business partner. We have a 50/50 partnership. Equal footing is essential for our mutual trust. Even if that means by legal definition, we’re not a woman owned business. We’re most proud of the work that comes from truly transdisciplinary disciplinary design processes.

We commit a lot of time to developing partnerships, relationships, and to building consensus. Jha D. can maybe can attest to that as a collaborator of ours. Or not, which you should tell me afterwards. We believe in decentralizing hierarchy and we lead our office by example. We believe in lateral processes, honest collaboration and transparency. We try to make the operational aspects of our business as open and accessible to our employees as possible. We have a salary ladder tied to titles and responsibilities. That is also something that’s constantly in flux and that our employees have a hand at manipulating. We commit time to the dialogue and mentorship. And I think because of the experiences we’ve had in previous offices we give our design team freedom that empowers rather than degrades our confidence, we strive to build a very diverse group of staff with different backgrounds, different educations and different perspectives.

Many of our projects exist within the margins of urban areas in former industrial sites on sacred indigenous sites and reservations and marginalized neighborhoods and segregated cities like Omaha and Detroit, Milwaukee, St Louis and Minneapolis. The way our city Minneapolis, in particular, has changed over time is a huge undercurrent that affects which projects we’re pursuing, which clients we’re seeking relationships with, which clients we feel comfortable challenging, who our design partners are, and how we approach community participation in different parts of the city– two cities, St Paul also – I won’t ignore them. Focusing on the physical perceived and dynamic issues of our time or actively trying to change how our way of working and designing is actually addressing these issues.

How we work is also a strategic choice. Ross Altheimer, who many of you know, is a UVA alum and my business partner. We have a 50/50 partnership. Equal footing is essential for our mutual trust. Even if that means by legal definition, we’re not a woman owned business. We’re most proud of the work that comes from truly transdisciplinary disciplinary design processes.

We commit a lot of time to developing partnerships, relationships, and to building consensus. Jha D. can maybe can attest to that as a collaborator of ours. Or not, which you should tell me afterwards. We believe in decentralizing hierarchy and we lead our office by example. We believe in lateral processes, honest collaboration and transparency. We try to make the operational aspects of our business as open and accessible to our employees as possible. We have a salary ladder tied to titles and responsibilities. That is also something that’s constantly in flux and that our employees have a hand at manipulating. We commit time to the dialogue and mentorship. And I think because of the experiences we’ve had in previous offices we give our design team freedom that empowers rather than degrades our confidence, we strive to build a very diverse group of staff with different backgrounds, different educations and different perspectives.

We’re thankful and we verbalize that gratitude often and we really mean it. So, this is who we are right now. We’re six full time, two part time people. We share a commitment to building a culture of fun. So you have to answer certain questions in our interview process about what you think is fun. We share a passion for the process of design and we believe that research, experimentation and creative inquiry is a critical and under-considered component of our practice.

So the two projects I’m going to talk about, Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C. and the Minnesota River Cultural Resources Plan are a bit different than the ones we’ve looked at so far. And I’m really glad that I chose them for that actually. This is a university, it’s the nation’s only higher education institution where all programs and services are specifically designed to accommodate the deaf and hard of hearing students.

We worked with Mass Design on this. They were the lead. So to begin this process, the pieces that were organizing us were this knowledge that deaf people create new modes of knowing, sensing, and making that are unique to the world. The underlying mission-driving question is ‘what types of spatial strategies can create a heightened visual tactile means of spatial orientation to deepen sensory knowledge for all?’

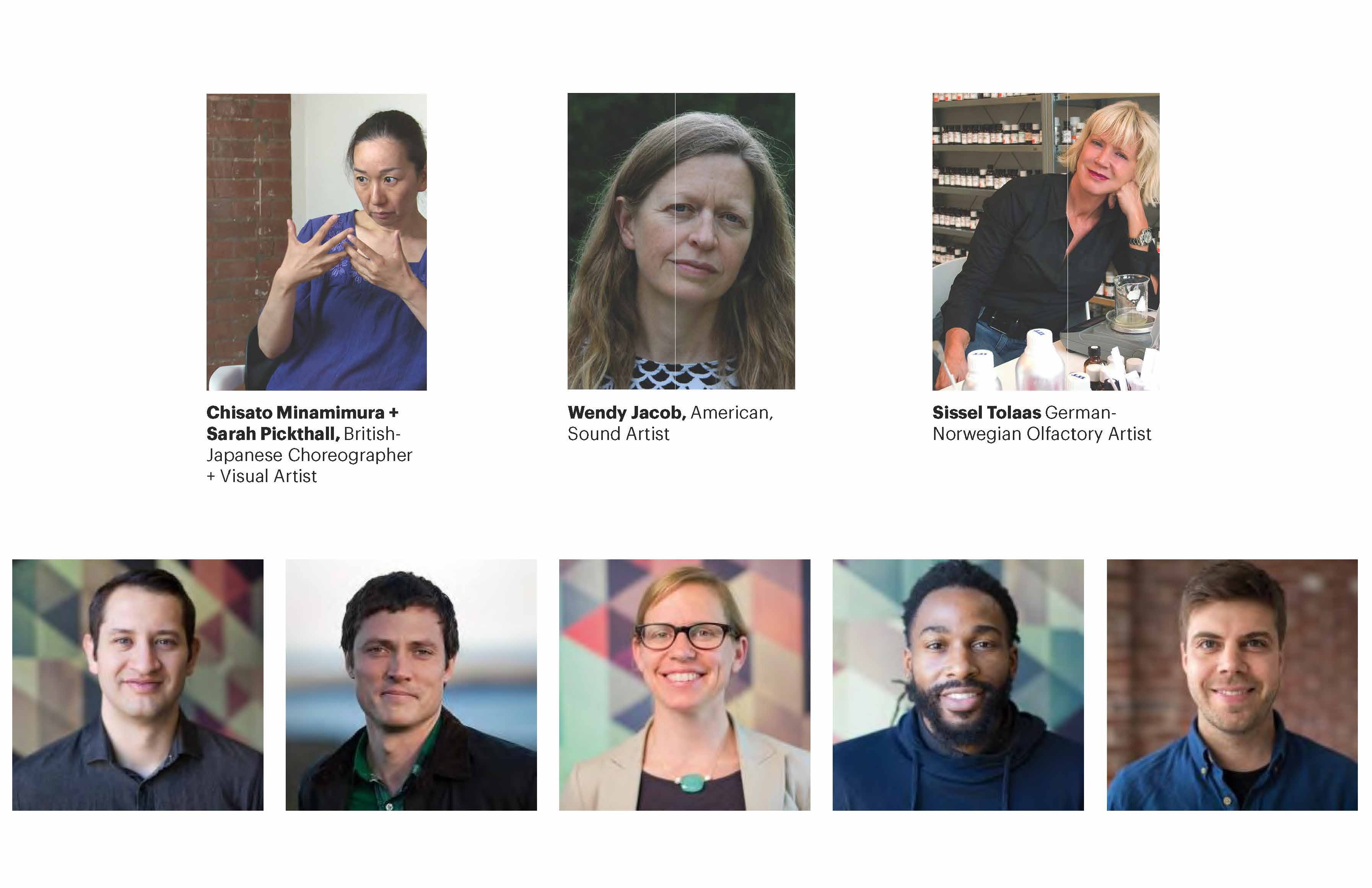

So the project was an international design competition with four finalists teams selected to participate. It was a four month process and unfortunately because the university underwent a leadership change, right as we were finishing the competition, they didn’t actually let us deliver the competition on the day it was due. Instead they started all over. Can you imagine that? Four months of work and then ‘great, you’re still our select teams, but we’re starting this competition over.’ So we did it again. You know, that’s also another lecture. Our team was led by Jeff Mansfield, a deaf architect with Mass Design Group and it included three sensory artists each focused on a different sense in their individual work.

So the two projects I’m going to talk about, Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C. and the Minnesota River Cultural Resources Plan are a bit different than the ones we’ve looked at so far. And I’m really glad that I chose them for that actually. This is a university, it’s the nation’s only higher education institution where all programs and services are specifically designed to accommodate the deaf and hard of hearing students.

We worked with Mass Design on this. They were the lead. So to begin this process, the pieces that were organizing us were this knowledge that deaf people create new modes of knowing, sensing, and making that are unique to the world. The underlying mission-driving question is ‘what types of spatial strategies can create a heightened visual tactile means of spatial orientation to deepen sensory knowledge for all?’

So the project was an international design competition with four finalists teams selected to participate. It was a four month process and unfortunately because the university underwent a leadership change, right as we were finishing the competition, they didn’t actually let us deliver the competition on the day it was due. Instead they started all over. Can you imagine that? Four months of work and then ‘great, you’re still our select teams, but we’re starting this competition over.’ So we did it again. You know, that’s also another lecture. Our team was led by Jeff Mansfield, a deaf architect with Mass Design Group and it included three sensory artists each focused on a different sense in their individual work.

Thank you Maura for bringing up the importance of gratitude. -- J.B.

The University is a point through which the entire global visually performed realities of the deaf community are being drawn to the surface. This artistic and cultural production of the deaf community, what Jeff often refers to as ‘deaf craft,’ has the potential to deepen sensory knowledge for all of us: knowledge of how we are in the world, even though we are hearing people.

The university kicked off the competition through a series of workshops that totally reset the way that we thought about this project, and they’re some of the most powerful questions I’ve ever encountered as a designer. Even though most teams had deaf architect on the team, the majority of us had very little exposure to deaf culture. They did a whole series of workshops that were all about knowing through touching and feeling and other ways of communicating without words.

The university kicked off the competition through a series of workshops that totally reset the way that we thought about this project, and they’re some of the most powerful questions I’ve ever encountered as a designer. Even though most teams had deaf architect on the team, the majority of us had very little exposure to deaf culture. They did a whole series of workshops that were all about knowing through touching and feeling and other ways of communicating without words.

We walked through the campus to understand how deaf and blind people see through different sensory tactics. We worked with clay and our hands. We touched each other a lot. The professor in the upper left–you see he’s getting information touched into his back.

This is no longer groundbreaking, but it’s a relatively newer form of communication. So if American Sign Language or ASL is talking through your hands and space touching air, this is called the Pro- Tactile, so PT-ASL is touch that is practiced on the body, and it can connect small groups of people in communication rather than just one-to-one. So as I’ve said, I’d never touched more people in one day in the most gentle, intentional and respectful way. I had never experienced anything like it and I haven’t since.

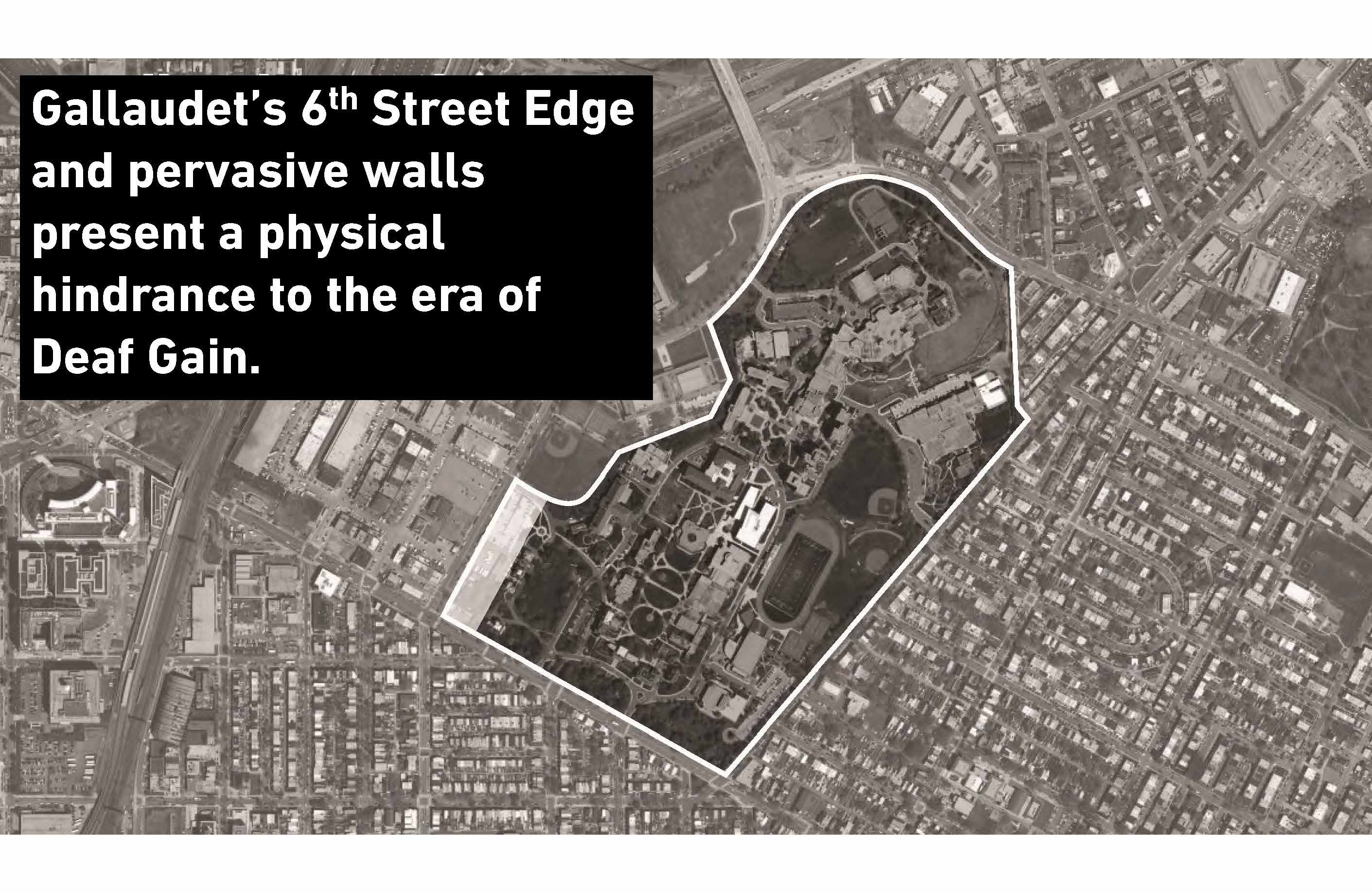

The original campus in Northeast DC was designed by Olmsted in 1866. It’s identified as a historic district on the national register. The brief for the competition was to reimagine the historic core to open up this western edge, which is grayed out or whited out between the university and the city.

That was led by a regional developer JBG and the teams were asked to design a new signature building at the corner of Florida Avenue and sixth street Northeast. Because the campus isn’t currently being very responsive and expressive of the rich relationship between deaf and hard of hearing experiences in the built environment, the teams were asked to integrate the University’s super innovative emerging approach to architecture and planning known as Deaf Space Principles. So we were asked to integrate that into the new architecture and to the redesign of the campus.

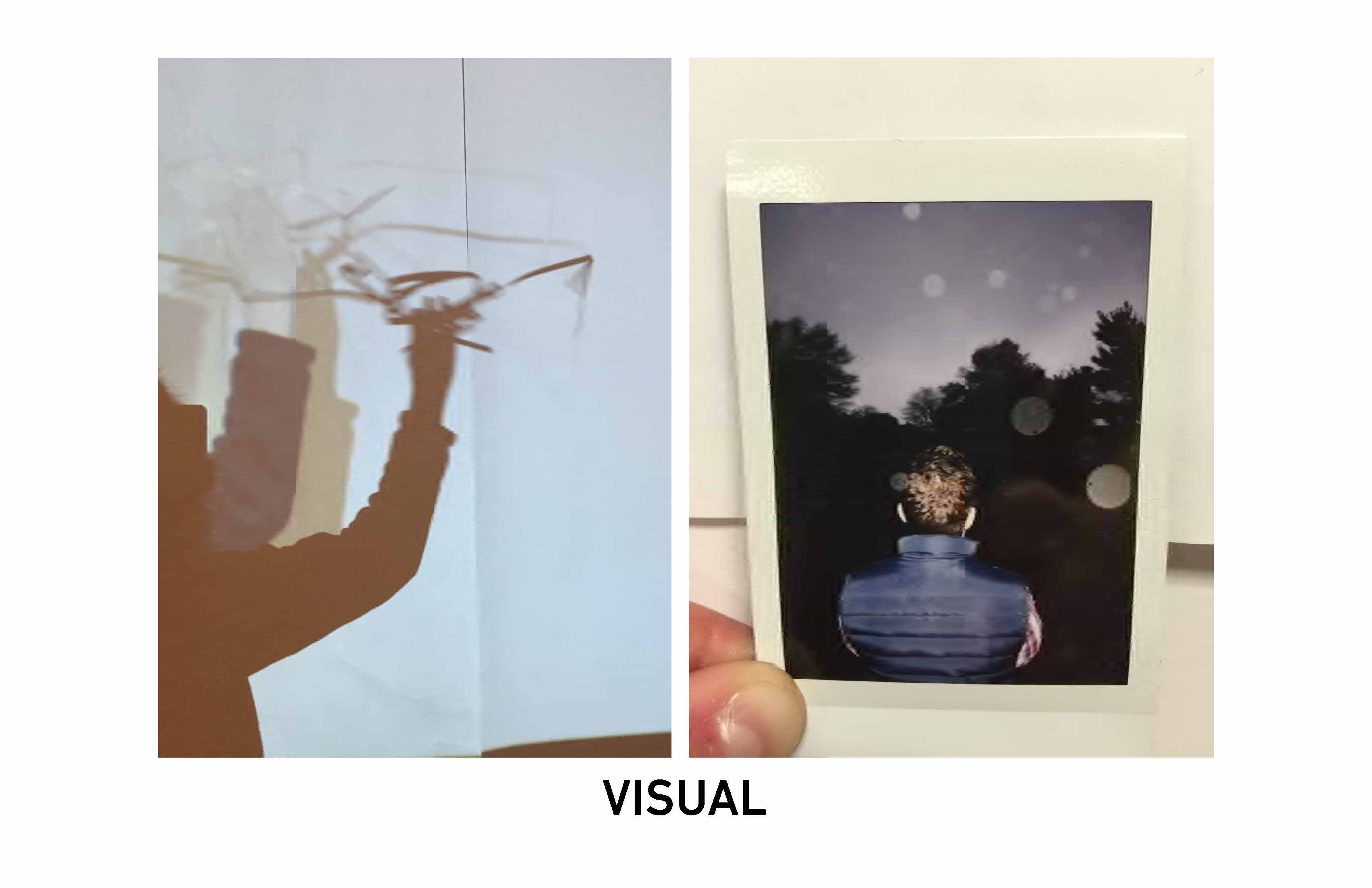

During the first two months, the design teams were also asked to host a series of workshops. Drawing on the expertise in sensory research of each of our artists, collaborators, we designed a set of three immersive environments and campus mapping exercises. The first was our visual workshop.

This is no longer groundbreaking, but it’s a relatively newer form of communication. So if American Sign Language or ASL is talking through your hands and space touching air, this is called the Pro- Tactile, so PT-ASL is touch that is practiced on the body, and it can connect small groups of people in communication rather than just one-to-one. So as I’ve said, I’d never touched more people in one day in the most gentle, intentional and respectful way. I had never experienced anything like it and I haven’t since.

The original campus in Northeast DC was designed by Olmsted in 1866. It’s identified as a historic district on the national register. The brief for the competition was to reimagine the historic core to open up this western edge, which is grayed out or whited out between the university and the city.

That was led by a regional developer JBG and the teams were asked to design a new signature building at the corner of Florida Avenue and sixth street Northeast. Because the campus isn’t currently being very responsive and expressive of the rich relationship between deaf and hard of hearing experiences in the built environment, the teams were asked to integrate the University’s super innovative emerging approach to architecture and planning known as Deaf Space Principles. So we were asked to integrate that into the new architecture and to the redesign of the campus.

During the first two months, the design teams were also asked to host a series of workshops. Drawing on the expertise in sensory research of each of our artists, collaborators, we designed a set of three immersive environments and campus mapping exercises. The first was our visual workshop.

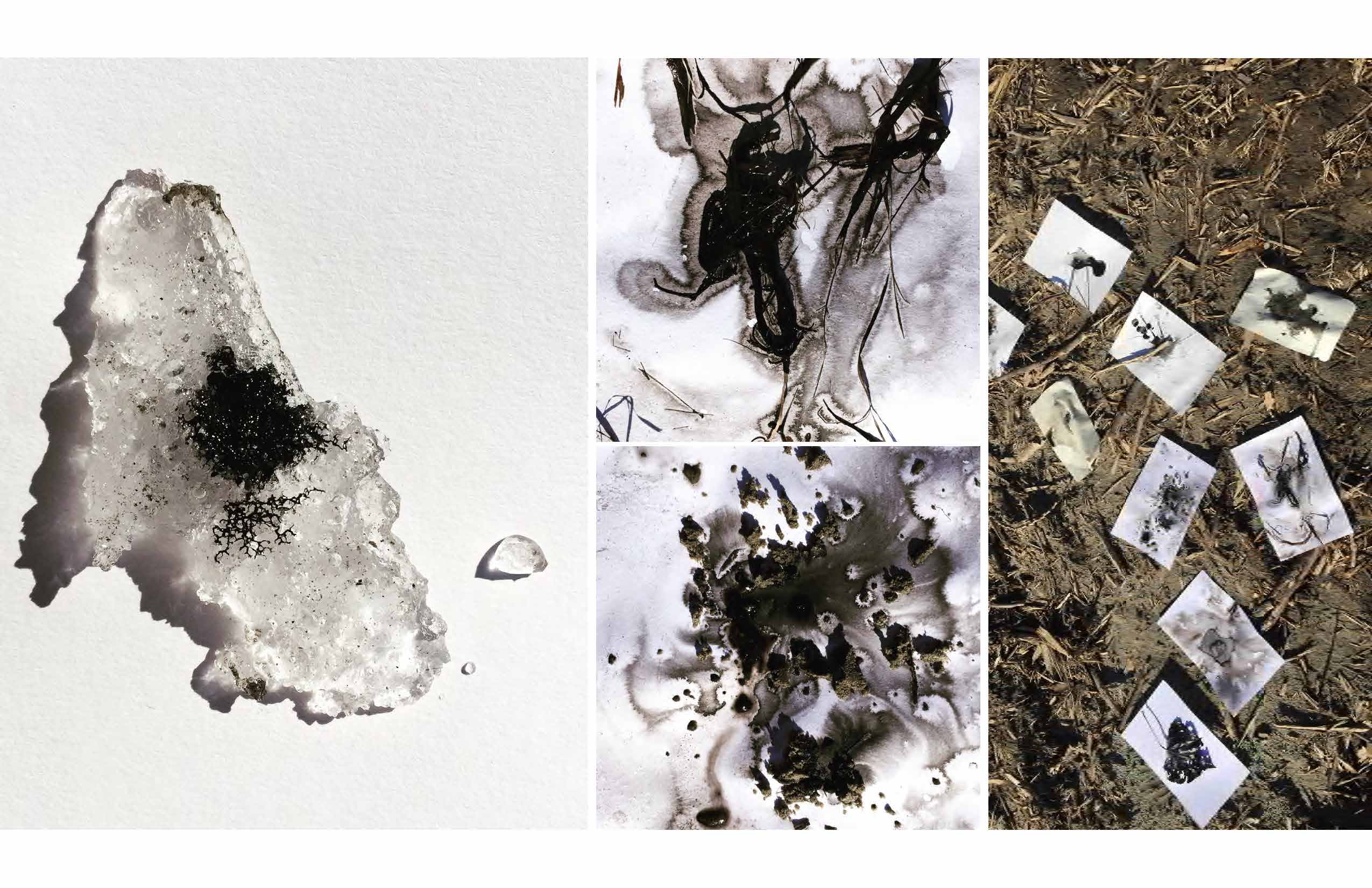

This was a video time-lapse recording and projection space that people moved through. It recorded your body moving through the space and it replayed back your shadow on delay, two shadows on delay. So as you moved through this space, there was a visual echo. Then we went out into the campus and paired up people together with a Polaroid camera. Nobody could speak. We asked one person to stop when they found something spectacular or notable in the landscape. And the other took a Polaroid of that and then they put it on a map.

Back in one of the buildings, the sound vibration room was a series of two subwoofers connected to a sound station where we had multiple tracks, hip hop, opera, classical music, monkeys, heavy metal, and people could feel the difference in those sounds through the vibration of the balloons on the subwoofer. I’ll play some of the sound: imagine you couldn’t hear that. but the way that the sound worked in these balloons, you could really feel it. You’ll have to take my word.

The third experience was olfactory. So Cecil, the olfactory artist sent us a never before created scent from some factory in New Jersey. To me it smelled like grape soda and winter green gum. I heard someone else say it smelled like Pine Sol. We created this interior quiet space where people could enter. It was pitch black, so some people did not like being in that space. The idea was to eliminate all other sensory inputs other than just the olfactory smell. Then we planted the smell on these little sticks around campus. People were walking a trajectory and had to pin a stake where they smelled that smell.

Back in one of the buildings, the sound vibration room was a series of two subwoofers connected to a sound station where we had multiple tracks, hip hop, opera, classical music, monkeys, heavy metal, and people could feel the difference in those sounds through the vibration of the balloons on the subwoofer. I’ll play some of the sound: imagine you couldn’t hear that. but the way that the sound worked in these balloons, you could really feel it. You’ll have to take my word.

The third experience was olfactory. So Cecil, the olfactory artist sent us a never before created scent from some factory in New Jersey. To me it smelled like grape soda and winter green gum. I heard someone else say it smelled like Pine Sol. We created this interior quiet space where people could enter. It was pitch black, so some people did not like being in that space. The idea was to eliminate all other sensory inputs other than just the olfactory smell. Then we planted the smell on these little sticks around campus. People were walking a trajectory and had to pin a stake where they smelled that smell.

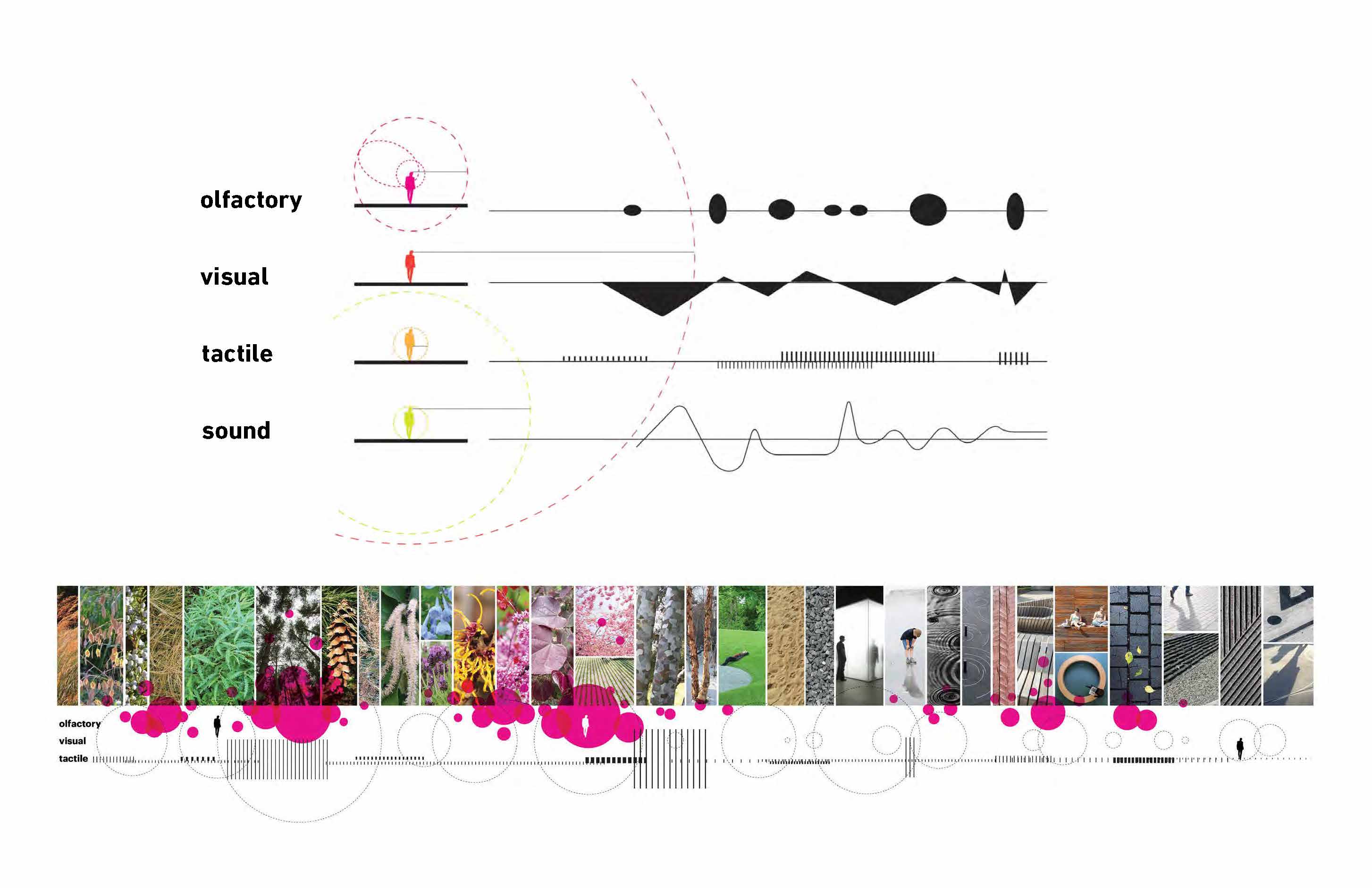

The whole point of the workshop was to begin to map and understand how sensory inputs affect the way that we move through and experience our exterior environment, once we’ve awakened our body to particular senses and a deeper physical awareness of what inputs we’re getting. There is a human scale to each of the senses and paying close attention to the nuances between them and whether they’re connected or episodic, or how the sensory input was changing throughout the day, or you can imagine how sensory inputs change with the season or the weather. By mapping those existing conditions across the campus, we were able to start to recalibrate and to test a heightened visual tactile means of spatially orienting. We began overlaying different strategies together to direct or impact potential trajectories of movement.

With designers, client and stakeholders all very much in the game, this intricate and visceral means of understanding the project's challenges and potential is the ultimate example of a holistic collaboration. -- J.B.

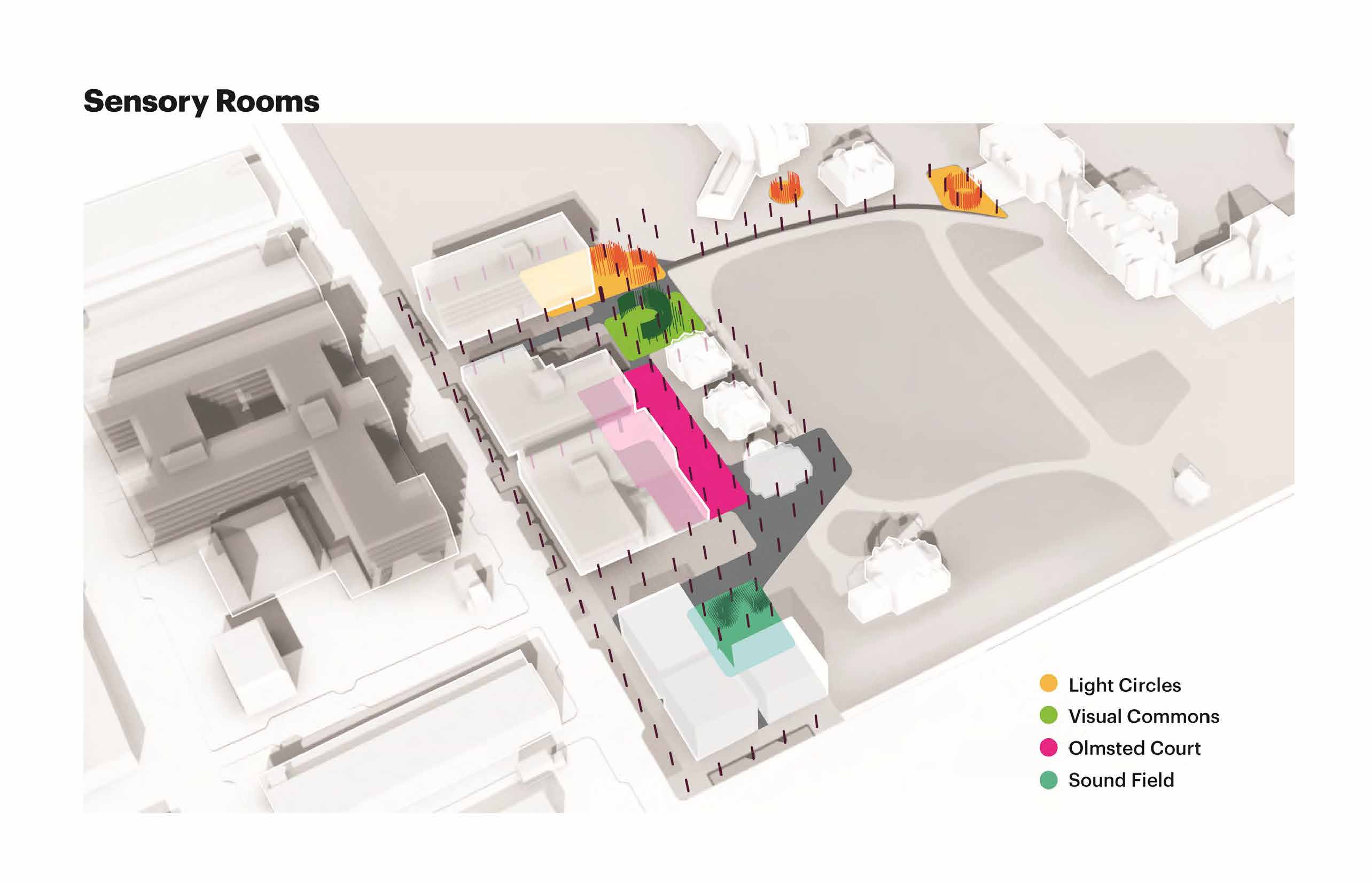

The overall campus redesign approach was organized around three simpler primary ideas: First, to preserve and restore historic foundations. Second, to activate and empower through new connections, so respectfully breaking the boundary of these historic walls. This whole campus was walled and elevated. The power dynamics that kind of architecture puts on a city, and puts on pedestrian, is pretty huge. So breaking the walls to create bilingual and bicultural exchange between the university in the neighborhoods surrounding it and to physically reconfigure the current sense of isolation and otherness that the architecture was creating was fundamental. And third, to heighten interaction between or through this bilingual zone with sensory paths and rooms. But because we were limited by the ability to create new pathways or realign the historic pathways, we nested layers of sensory paths into that historic infrastructure.

You can see how that is deployed across the overall campus master plan. This was really a part of the first four months of work. The second four months of work asked us to focus on that developer seam between the campus and the city. So as we continued to work (for free) we developed a much more honed in and specific idea about this bilingual threshold, and we did that through thinking about the five stages of deaf experience. And this was really Jeff Mansfield leading this idea and us listening and working with him to help spatialize it on the ground.

So we spatialized it both horizontally across the public realm and also vertically through the signature building that was holding the corner there. We begin with awareness on the street, as you move into the campus, you’re heightening this vulnerability with ways of experimenting, perhaps communicating with people. We were asking, ‘how can we prompt that or encourage that in the landscape?’ Then you move into the campus, theoretically with more fluency. So within this bilingual zone, which was strategically shifted directly at that scene between the historic campus and the backside of this development zone. We didn’t have enough room on the street. We also didn’t want the front of the development buildings to taint the way that this landscape could be designed. So we put it on the backside, and we developed these four rooms as a pilot project or catalyst. The idea being that we’re spreading this grid of new infrastructure across this space and that the digital media, the arts programs that Gallaudet is forging, using deaf craft, could begin to display and take ownership of the spaces in similar or different ways.

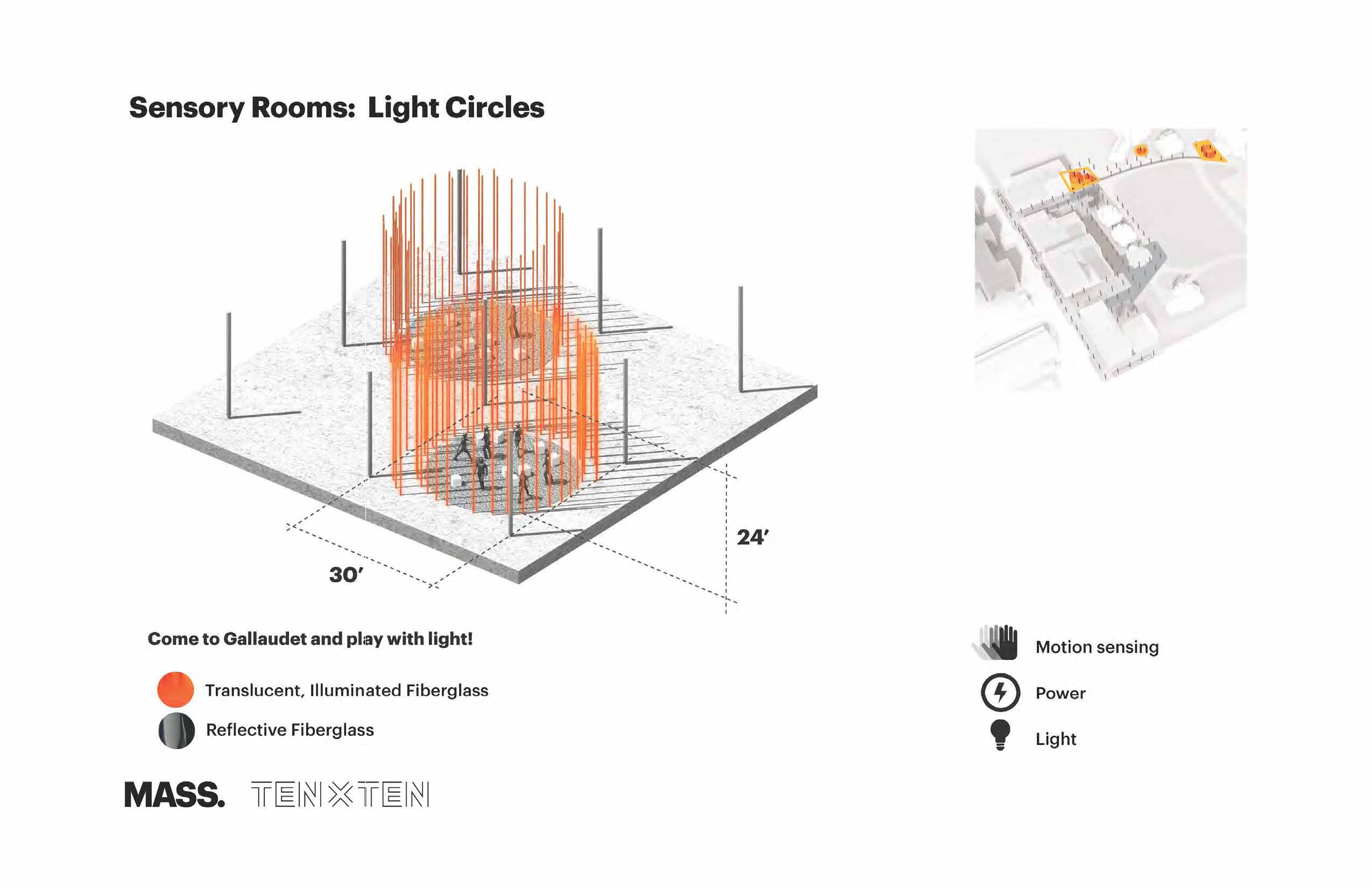

For example, one of the spaces we designed this working with our artists group was light circles, so nested within our larger infrastructural grid was the smaller sensory grid. These were light circles with fiberglass tubes and lighting and motion sensors. So the more people in these spaces, the brighter these small rooms glowed. Or a visual commons, in the spirit of this campus’ amazing history of protest, we created a larger gathering space using interactive kiosks where people could type: it’s like on our iPads or iPhones we used a program called big and it made the text big. This would make the text really big and you could text in these kiosks and have a conversation in the round, like this.

The second project I’ll talk about is the Minnesota River Cultural Resources Interpretive Plan. Seventeen miles of the Minnesota River, just South of the twin cities. This site is Dakota Homeland and part of our team makeup included a Dakota multimedia artist, Mona Smith and an interpretive planner, Jim Roe. So our underlying guiding knowledge about this process project was that a central tenant of Dakota thinking is Mitakuye Owas’iƞ or “all my relations.” This worldview is one of profound respect and responsibility to the natural world that many of us can’t comprehend. Even though we’re landscape architects and we think we get it, we don’t get it. They’re literally related to the rocks, and to the birds. It’s a whole different way of seeing your role in the world. So we asked ourselves, ‘What is our role in telling stories that are not our own? How can landscapes reveal truth and heal communities? How can we rethink making place?’

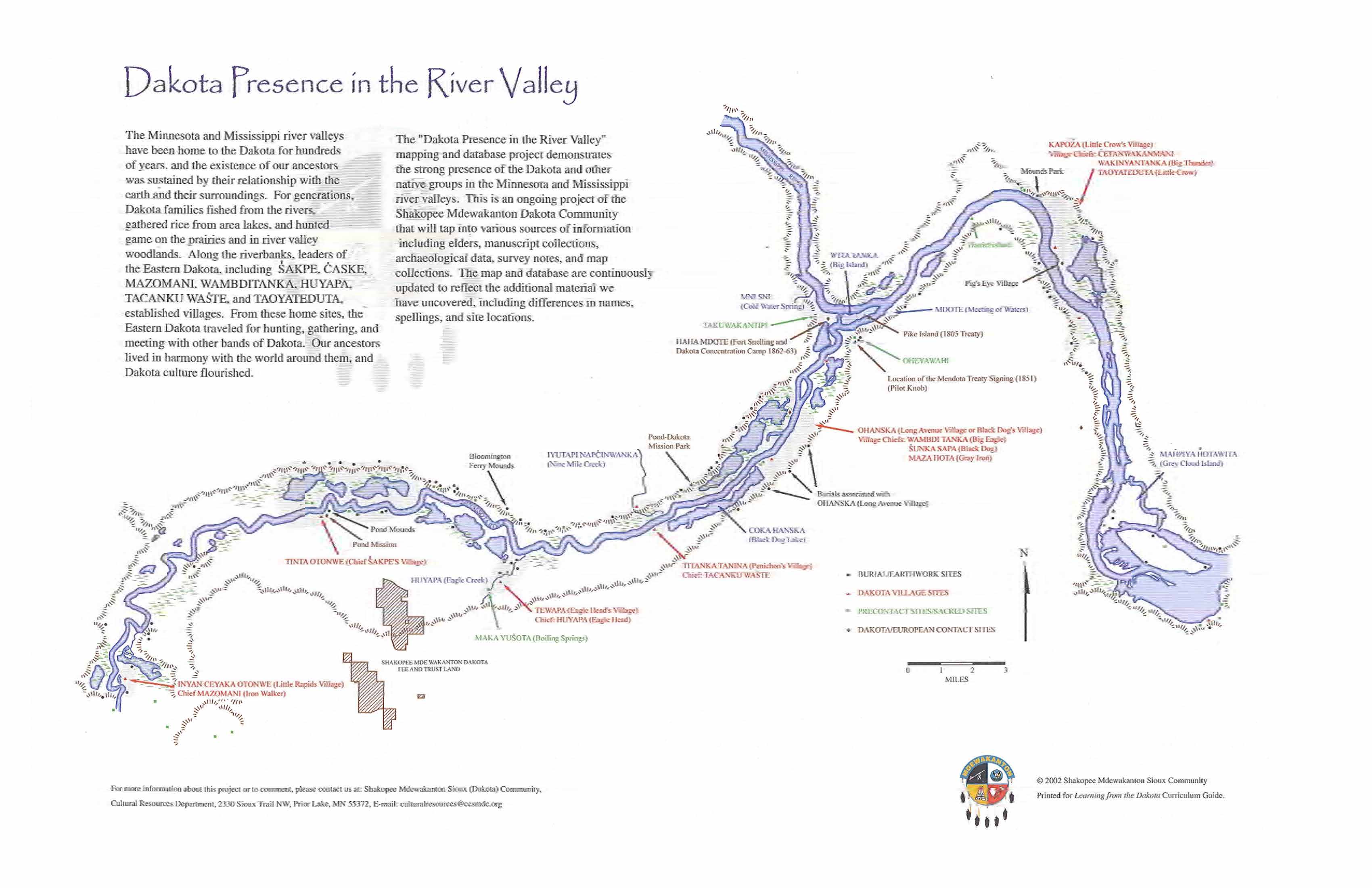

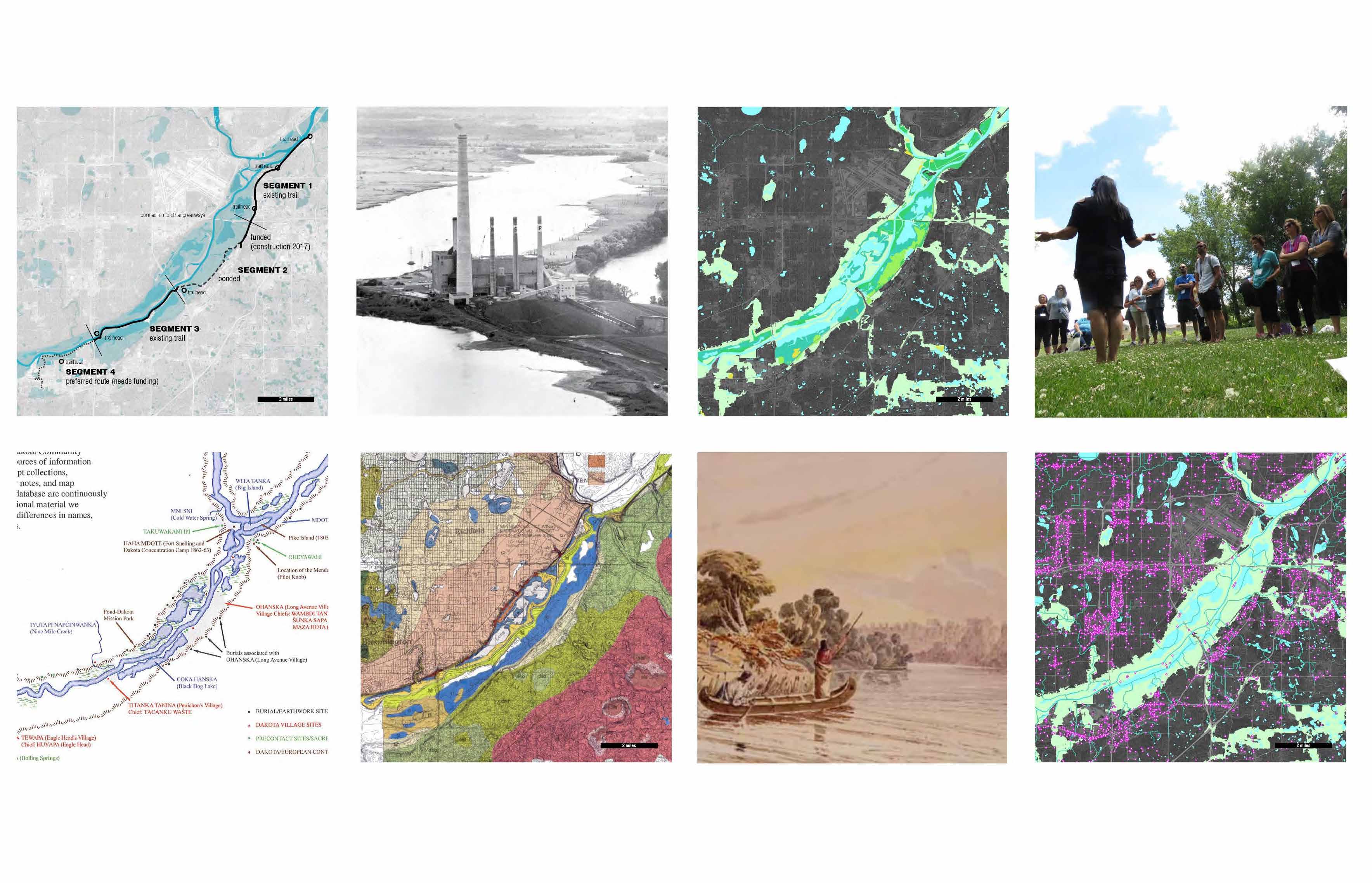

This is a map that shows to Dakota presence in the River Valley. It’s a map I didn’t see before starting this project, which is a crime. The fact that it’s not taught in our schools and not very accessible to anybody who wasn’t particularly looking for it. It’s embedded with history and places. They don’t often draw maps and putting a spot on the map is just not the way that they work. So it took us a while to get beyond thinking about ‘how do we document and research this project?’. And immediately in talking, even about pursuing it, we stopped and said ‘we have to do this project totally differently.’ The whole first two months has to be different than what we’ve done on every other project.

“Even though we’re landscape architects, and we think we get, we don’t get it.” I loved this idea from Maura because we can really see the open humility with which TENxTEN approaches their projects from the outset. Nearly each person on the panel touched on the ways in which they let the project and its constituents unfold into a place-driven design process, and I found Maura’s active rejection of expertise and the malleability of her firm’s site discovery tactics especially exciting.-- L.K.

While the traditional Western practice of cartography is not rooted in Dakota culture, contemporary Sisseton Wahpeton Dakota storyteller and media artist Mona Smith's Bdote Memory Map project (2013) marks a series of sites that have special meaning to the Dakota people. The bdote area of the Mississippi and the Minnesota Rivers are where the two bodies of water meet and Smith's interactive web-based project, a collaboration with the Minnesota Humanities Center, includes videos, still photographs, text, links and blogs that collectively tell the layered narratives of places such as Pike Island, Fort Snelling and Coldwater Springs, all integral sites of Dakota history. For more explore the Bodote Memory Map︎︎︎

The dominant worldview sees the world or the universe as a resource, typically something that humans have power over, and with the resulting belief that places can be made. So definitions of placemaking from a non-native viewpoint often talk about humans providing meaning to a location, thus making the place. To them, this is a very hierarchical point of view and not an indigenous way of looking at things. Making a place seems to them like disrespect. It seems like the height of human arrogance. You can see how this totally starts to flip the way we’ve been taught perhaps, or the power of actually asking questions about what we’ve been taught. So as I said, we proposed to do this differently. We took the first two months we biked, we walked, we kayaked. We did led meditation down in the river Valley. We did listening sessions with all the four primary Dakota communities who identify this with this place as their Homeland and their creation story.

Vanessa Watt’s article, “Indigenous Place- Thought and Agency Amongst Humans and Non Humans (First Woman and Sky Woman Go On a European World Tour!)” has radically restructured the way I see the world around me, particularly surrounding the Western divide between epistemology and ontology and the concept of Indigenous (particularly Anishnaabe, Watt;s heritage) place-thought. An amazing read that will open up vast chasms of doubt in our own Western concepts of self and knowledge of place. -- M.V.

Maura and I worked together on a project with the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. We encountered a very, very old wall in gaining their trust. Building trust, we learned, takes time in and of itself. Along the way, you slowly glean glimpses of their story but still wait for the day you are let in. Patience. -- J.B.

And of course, we did research in our typical mapping alongside that. But it was framed in a very different way and came after all of this other listening. The river Valley in historic Fort Snelling, which is at the crux of the two rivers, played a critical role in the U S Dakota war of 1862. And the aftermath of that war can still be felt today in every conversation we had about this project. You could feel it. So the confluence, called Bdote, of the two rivers is both a place of Dakota spirituality and history. It’s a place where they believe their people began. But it is also the place where almost 1,700, mostly women and children were forced into a concentration camp, where all but a few protected Dakota groups were loaded onto steam boats and exiled to South Dakota, and where two Dakota chiefs were hung. It’s a huge source of pain, intergenerational pain over time.

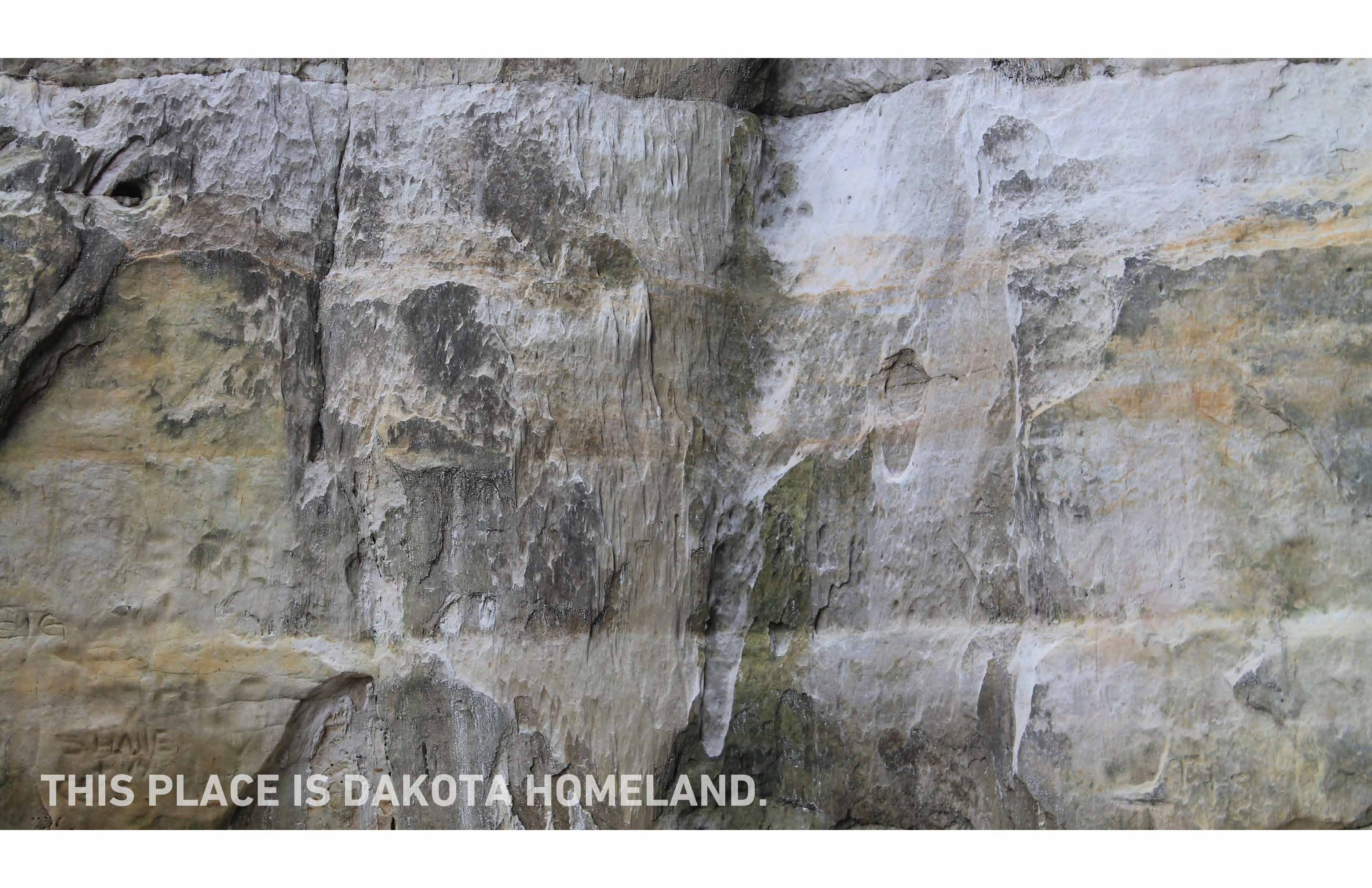

We were asked in the most respectful of ways to spend time there to learn from it, and so we did. We tried video, we did photography, and through this process we learned a little bit. We are not, by any means, experts, we have a long way to go. But we learned a little bit about what kinship actually means.

We were able to see reverence in a totally different way, and learned that our ways of seeing place and of seeing landscape are fundamentally different from an indigenous way of seeing and that there was huge value in understanding that. This helps to kind of explain a little bit perhaps why dominion over something is not a Dakota concept, why placemaking is a problem from their point of view. They believe they’re always in a relationship to a place, one that’s centered around reciprocity and respect.

We were able to see reverence in a totally different way, and learned that our ways of seeing place and of seeing landscape are fundamentally different from an indigenous way of seeing and that there was huge value in understanding that. This helps to kind of explain a little bit perhaps why dominion over something is not a Dakota concept, why placemaking is a problem from their point of view. They believe they’re always in a relationship to a place, one that’s centered around reciprocity and respect.

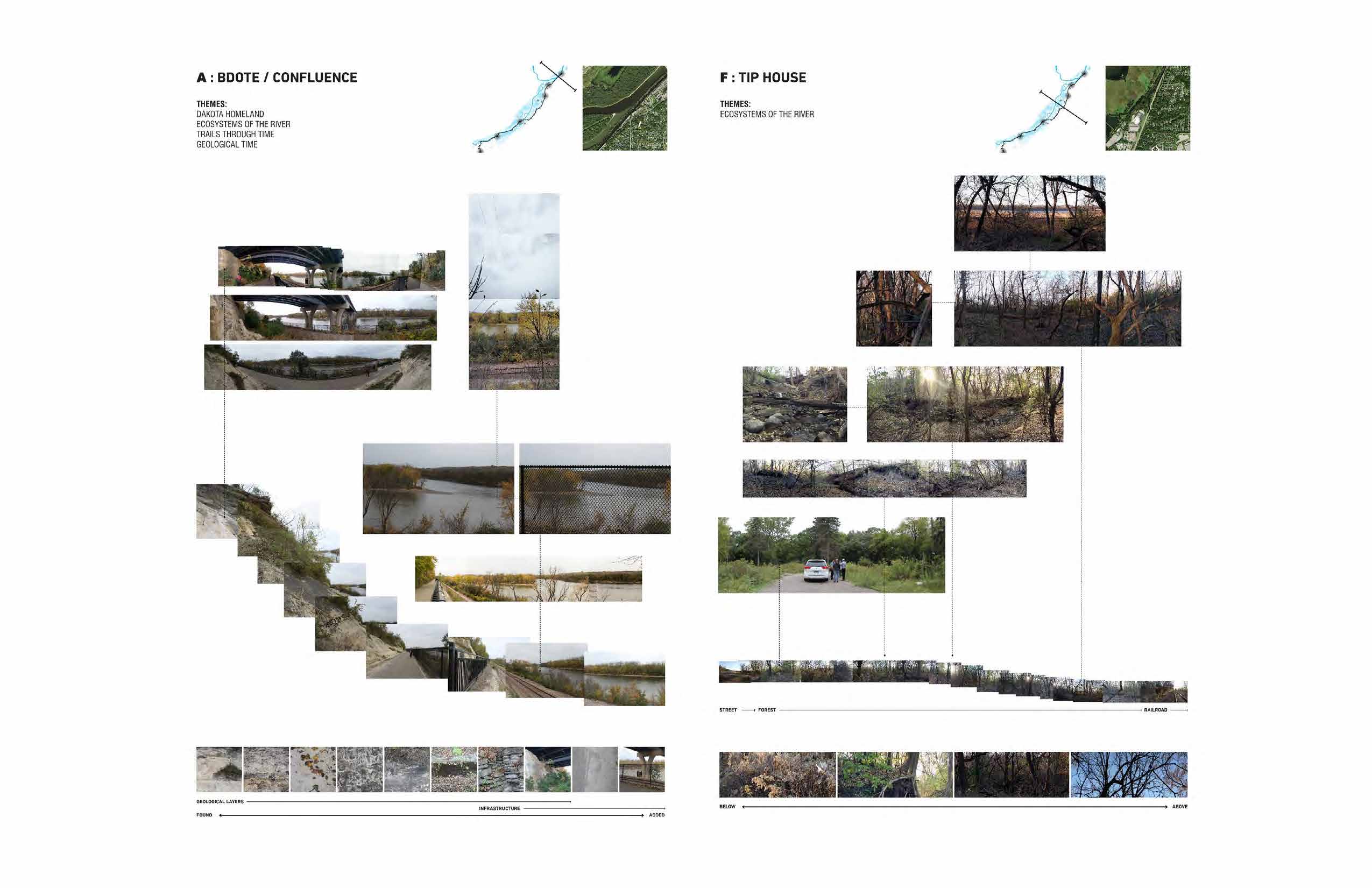

It’s a 17-mile stretch starting at the Mississippi River, passing through the confluence and then South along the Minnesota River. It passes through three different cities and they were looking for eight nodes, or trail heads. So we photographed it in a lot of different ways: details, large scale. We videotaped it. We did experiments with dry ice to try to map the wind, the differences between being on a bluff and being in a river valley. We brought drawing paper down and ink and we made drawings out of the materials, in different seasons, we got muddy, we played with the snow. We really did try to spend time in this place in a different way.

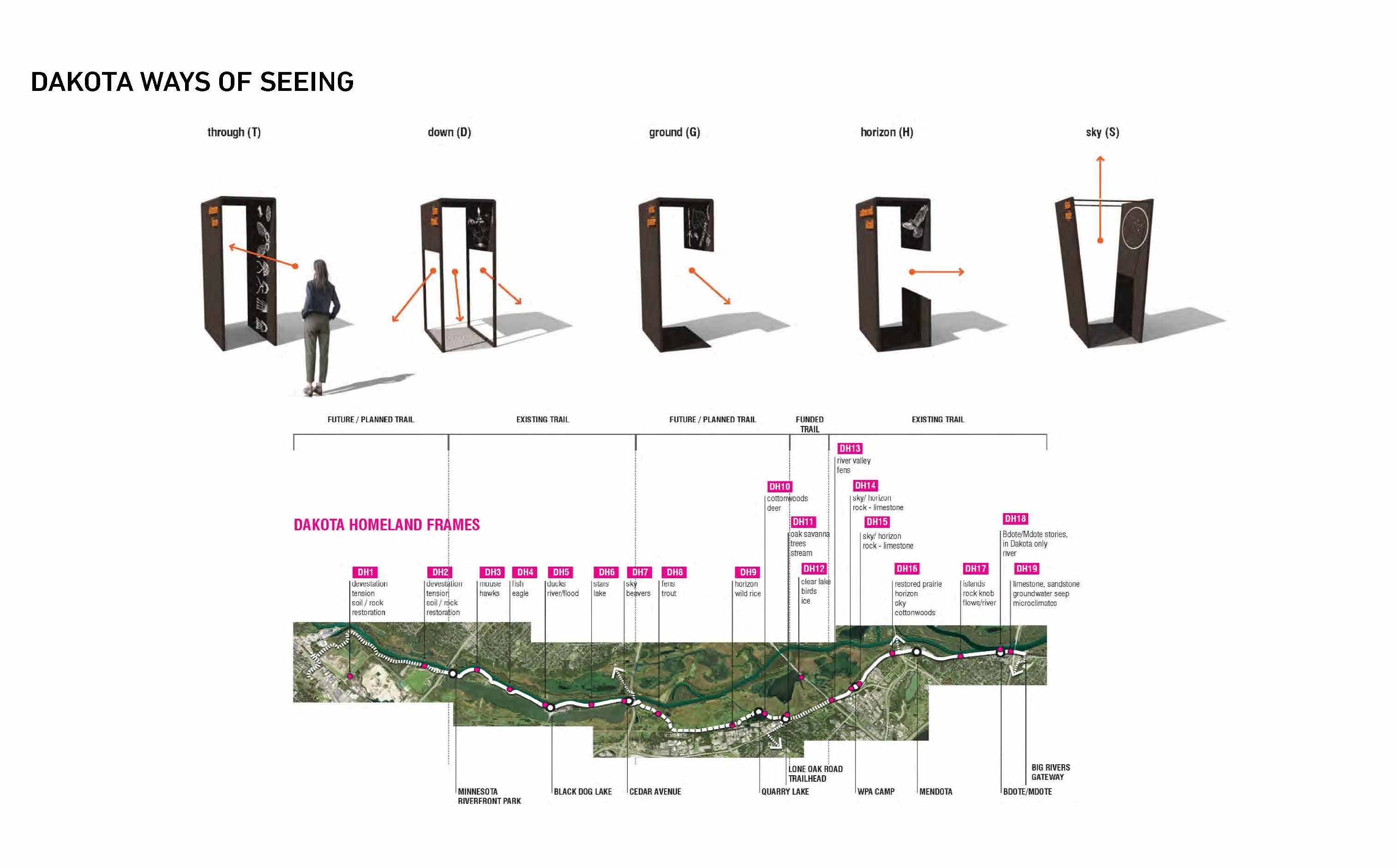

Here’s some of the typical mapping we did. So again, these eight nodes and honing in on what stories should be told at those nodes. I think the single thing we are most proud of for this project was not so much the designs we did at each of these nodes, but the trail-wide approach that grounded this place as Dakota Homeland. And that there were three overarching strategies embedded in everything: in the language of the trail, the markings, the standard materials, the signage.

Here’s some of the typical mapping we did. So again, these eight nodes and honing in on what stories should be told at those nodes. I think the single thing we are most proud of for this project was not so much the designs we did at each of these nodes, but the trail-wide approach that grounded this place as Dakota Homeland. And that there were three overarching strategies embedded in everything: in the language of the trail, the markings, the standard materials, the signage.

There is some level of bravery needed to tackle the issue of knowing who we are designing for. The multiple means described here like intentionally atypical mapping, reflect a willingness to ferret out connections. Does diversity in site inquiry lead to a diversity of social associations? Dam skippy. -- J.B.

Each did these three things that attempted to extend one’s time in a place. So one, these pull-offs, or gathering nodes along the side of the pathway, are trying to orient people towards the landscape or towards different ecological zones that are of importance and significance. Two, heightened sensory experience, again, through embedding new kinds of plants into the landscape delicately and again using signage to help focus different sensory perceptions outward and to offer new perceptions. So framing, for example, sites like historic Fort Snelling or Pike Island, the place of the concentration camp, from across the river. Talking and interpreting on this site why those places are significant. We made this series of signs particularly for Dakota ways of seeing that framed views through something or down at the ground or at the horizon or at the sky so we could begin to make more of a circular experience out of the materials of this place, out of the cosmos and the animals and the Mitakuye Owas’iƞ way of seeing the world. Thank you.